Rapid urbanization in Africa presents numerous challenges for municipal and national governments. How will cities house and feed their new arrivals? Will they have places to work? How will they get from point A to point B? All too often, the pace of urbanization exceeds the pace at which governments come up with answers to these questions, especially in the arena of public transportation.

Where African cities lack public transit services, entrepreneurs step in to fill the gap with paratransit services. Although policymakers across the developed world tend to use the word paratransit to refer to services for people with disabilities outside the regular transportation system, it has a different meaning in the context of the developing world. As Roger Behrens, Dorothy McCormick, and David Mfinanga define it, paratransit describes “a flexible mode of public passenger transportation that does not follow fixed schedules, typically in the form of small- to medium-sized buses.” Paratransit services take many names depending on the city: paratransit buses in Nairobi are called matatus, their counterparts in Dar es Salaam are called daladalas, and Cape Towners call their paratransit services mototaxis.

African paratransit services display two sides of inequality: on the one hand, paratransit can help alleviate the inequality built into formal public transit systems by being responsive to actual demand; on the other, paratransit often perpetuates inequality through rampant sexual harassment, unsafe driving practices, and high greenhouse gas emissions. As a result, policymakers must consider modernizing public transit systems and improving regulations on them.

“Segregation Now and Forever”

Europeans often designed colonial cities in Africa to maximize segregation, keeping the wealthy white settlers away from the poor black masses, and transportation infrastructure followed that segregation. Nairobi serves as a convincing example. As the British took the best land for their private residences (taking advantage of better weather in the northwest of the city), they built their transit network to facilitate the commute to the central business district, as the city’s main trunk route connected the CBD and the British suburbs. Meanwhile, in an attempt to keep Africans from moving to Nairobi, the British forced them into low-quality housing on the periphery of the transit network.

Similarly, the British made no investment in public transportation for the city’s African population, instead developing a road network that focused on individual means of transportation, from horses to cars. Since Africans could not afford cars, they could not access the city’s transportation network. This fit a wider pattern within colonial transportation networks: colonizers built most transportation infrastructure to transport raw materials from their production sites to ports for export, benefitting the colonizers while doing nothing for local populations.

The post-colonial Kenyan government has not done much better. Although the newly independent state did set up bus networks, these mostly serve routes within the CBD and between the CBD and the wealthy suburbs, failing to meet demand in the slums, where the majority of the population actually lives. Even if slum residents had access to bus routes, they likely could not afford the steep fares. Interestingly enough, a new class of wealthy Africans emerged, moving to the suburbs that had formerly housed the British and taking up car ownership. These new middle and upper classes advocated for the construction of new roads and upgrades to old ones, failing to solve problems of congestion while only reinforcing car usage, which remains limited to the wealthy few.

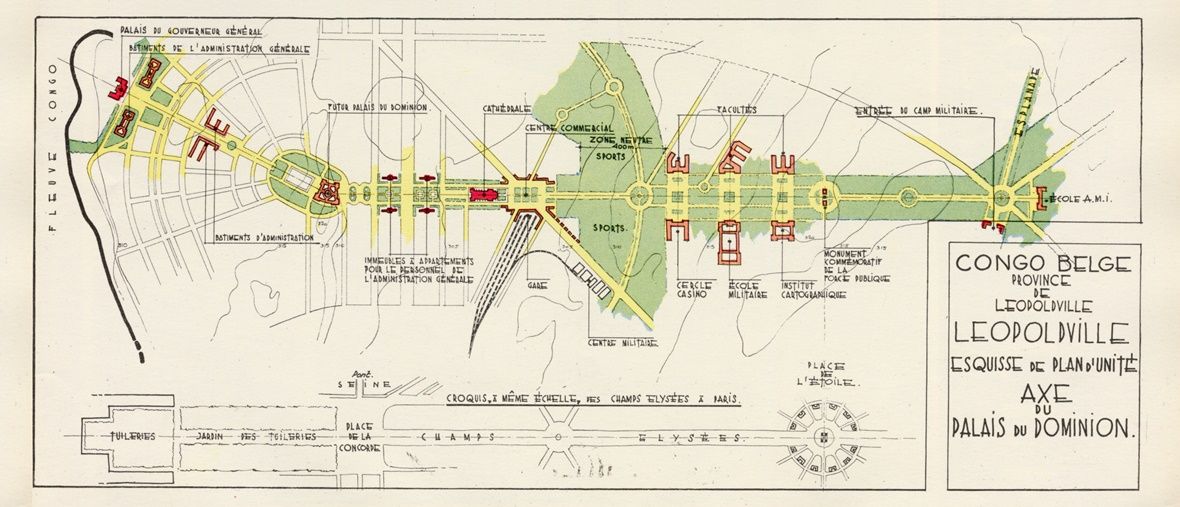

In Kinshasa, the story is similar. Kinshasa’s French rulers created a “cordon sanitaire” to separate the indigenous city from Western residential and business districts. Although this initially emerged from patterns of white supremacy and socioeconomic stratification, concerns about the spread of malaria soon turned this de facto segregation into de jure segregation. Plans for new development (including transit development) proposed satellite towns for Africans, disconnected and segregated from European residences and places of business.

When public transport systems did emerge in Kinshasa, planners did not focus on connecting local Africans to places of business. Instead, buses would only serve the two “monumental axes” of the European city, not the African satellite cities. Electric buses called gyrobuses (based on a mechanical gyroscope) would serve these two routes, although they quickly broke down in the tropical heat. Indeed, the gyrobus system seemed to promote colonial interests at the expense of Africans: an electric company lobbied heavily for their implementation to guarantee a market for electricity. After the failure of the gyrobus system, the government merely recognized the monopoly of other private minibus operators instead of establishing a formal public transit system.

In other cities, rapid growth on the outskirts has contributed to poor public transit. In Kinshasa, unplanned growth caught policymakers unaware, and the government failed to plan new road networks or public transit systems to keep apace. In cities such as Ouagadougou and Douala, public transport is concentrated along radial roads that do not serve the majority of the population. Because of the rapid growth, African governments have failed to build quality roads into newly urbanized areas, reducing the quantity and quality of public transit that is available for residents of these areas.

Paratransit and Equality

By offering service where public transportation is unavailable or unaffordable, paratransit helps to rectify the inequalities remaining from colonial-era segregation. In Nairobi, matatus serve almost 70 percent of all transit trips, precisely because they service low-income areas at more affordable prices and routes that may not have enough demand for regular public transit services. In Lagos, due to extremely poor public transportation, kabu-kabu services fill the massive void in affordable transportation systems. In South Africa, combis serve squatter settlements and shantytowns not served by traditional bus services. Indeed, paratransit services across Africa respond to demand much quicker than hidebound bureaucracies, creating routes in rapidly urbanizing areas that do not have other transit services before the government can (or is willing to).

Paratransit services also alleviate inequality by providing jobs for low-skilled workers. Each vehicle creates at least two jobs: a driver (who may or may not have a professional driver’s license) and a conductor to interact with passengers and collect fares, a position that does not require many formal skills. As a result, young men in cities with high levels of youth unemployment can find jobs in the paratransit sector. Paratransit also creates jobs indirectly: mechanics fix minibuses, gas stations earn extra revenue, and eateries along popular routes benefit from increased traffic along those routes.

Paratransit and Inequality

Despite all their benefits in alleviating inequality in transportation structures, paratransit services still perpetuate inequality in other ways. For one, sexual harassment is rampant in paratransit services across the continent. A Zimbabwean mother, Maureen Sigauke, explained in CityLab that conductors routinely shouted harassing remarks at women as they solicited passengers. Men and boys known as “touts” also engage in harassing behavior, such as commentary on women’s looks, sexual jokes, and even unwanted physical advances.

Sexual harassment and problems with touts aren’t limited to Zimbabwe. In Nairobi, matatus with stickers such as “A woman is like a common maize cob for every man to chew” and “Men are like oxygen: women cannot do without them” are frighteningly common. Conductors and drivers routinely flirt with female passengers because they perceive (often correctly) that the women have no option but to put up with the harassing behavior. Catcalling is often followed by laughter from male passengers, stigmatizing and embarrassing women even further. In the chaos of matatu stops, touts often separate mothers and children—a traumatizing experience in and of itself—before making fun of mothers for inadequately protecting their children.

General harassment often disproportionately affects women, too. Nairobi touts frequently make fun of their passengers for their socioeconomic status. These harassing statements not only reaffirm social divides, as many households cannot afford cars in the first place, but they also affirm inequality within the family, as men in households with only one car take the car, forcing women to ride increasingly unsafe matatus.

Unsurprisingly, many buses or motorcycles involved in paratransit operations are old and poorly maintained, without newer emissions-reducing features, which have large upfront costs. As a result, paratransit contributes disproportionately to air pollution in many African cities. Dar es Salaam presents an interesting case study: daladalas often run on leaded gasoline, which could lead to developmental problems in children and lead poisoning in adults. Concentrations of sulfur dioxide in Dar es Salaam bus stations are high enough to cause breathing issues within half an hour. This pollution disproportionately affects the people taking paratransit, who tend to be society’s poorest. Among those people, pollution impacts vulnerable populations, such as children and the elderly even more.

Paratransit operators have economic incentives to move as many people as quickly as possible to the next stop, as drivers often pay owners a fixed fee for the use of the vehicle and keep any remaining revenue. More people means more fares, and faster trips mean more trips in the same amount of time. A UN report on matatus in Kenya described a “devil-may-care mentality” among the “mad rush for passenger fares.” Matatu operators overload buses, stop in sidewalks or in the middle of roads, and ignore traffic laws in their quest for income. This phenomenon isn’t limited to Kenya: daladala operators in Dar es Salaam and mototaxi operators in Cape Town use a similar strategy.

This has several effects. First, people with disabilities do not have space to use paratransit services, drastically reducing their mobility. Second, bus overloading creates poor transit conditions for women with children and for the elderly. Third, buses often collide with pedestrians, leading to fatalities in many cases. Indeed, matatus contribute to 80% of pedestrian deaths in Nairobi. Since a disproportionate amount of lower-income people walk to work and school, this high fatality rate disproportionately impacts those lower on the socioeconomic ladder.

Regulation and Rapid Transit

While paratransit services play a large role in contributing to inequality through pollution, sexual harassment, and unsafe driving, they also provide large benefits to lower-income residents of African cities. With this in mind, policymakers throughout the continent cannot simply do away with the paratransit system, though they cannot leave the status quo in place either. Therefore, reforms to ensure that transportation systems continue to serve lower-income residents while making improvements in safety and efficiency are imperative.

Regulation of currently existing paratransit services presents one option for improving them. In Nairobi, the Michuki rules (named after Kenya’s transportation minister) imposed “no standing” policies, required paratransit operators to install seat belts and speed governors, and implemented licensing procedures. However, police corruption and bureaucratic infighting reduced enforcement of these rules, and unsafe matatus continued to operate. When laws like this are enforced, they work: accidents involving matatus dropped by 94% in the first three months after the implementation of the regulations. Consequently, the fate of the Michuki rules demonstrates the need for strong enforcement of existing laws, although this may be easier said than done. Additionally, countries could consider incentives to reward paratransit operators who meet certain safety or emissions metrics, thus encouraging some investment in better equipment.

Alternatively, policymakers have considered improving their public transit systems in consultation with paratransit operators to better serve low-income passengers (and improve safety and emissions) through bus rapid transit (BRT), with dedicated bus lanes, platform-level boarding, and fare collection points outside the bus itself. The experience of Dar es Salaam shows the benefits (and drawbacks) of a full-on BRT system. DART, Dar es Salaam’s BRT system (accompanied by investments to improve sidewalks and street crossings), reduced travel times for users by as much as 50 percent and won the 2018 Sustainable Transport Award, showing that sustainability and performance can go hand-in-hand.

However, Dar es Salaam’s system represented a significant investment, and BRT fares were 55 percent higher than corresponding daladala fares, meaning that the government would have to subsidize the service to make it more accessible. Indeed, many sub-Saharan cities cannot afford to entirely replace paratransit with bus rapid transit, so they could instead implement feeder-trunk services: paratransit that would connect less-travelled routes with less demand to trunk routes served by larger BRT vehicles, maintained by the state. Theoretically, such a model would combine “the efficiencies of larger vehicles” with “the demand-responsiveness of paratransit.” Despite their relative wealth, Cape Town and Johannesburg quickly realized that such a model was preferable, as paratransit served some areas much better than conventional bus services. Cape Town also employed the novel strategy of peak lopping, where it employed paratransit services to add capacity to key routes at peak hours for demand.

Concomitantly, less expensive infrastructure improvements (like dedicated and segregated lines for paratransit, off-street stations, and traffic management systems) could reduce unsafe driving practices that often result in fatalities. Targeted tax breaks and subsidized loans to paratransit operators could also help them to improve their vehicles for less than the cost of a full BRT system.

To reduce sexual harassment on paratransit, municipalities should invest in public relations campaigns to encourage women to report cases of sexual harassment and make clear that sexual harassment isn’t tolerated. To make this PR campaign effective, though, they need to massively improve enforcement of existing anti-sexual harassment policies, removing corrupt officers and actively punishing cases that move to trial. A move to more formalized transit systems (like BRT) can also reduce harassment, since these systems do not need the aggressive machinations of touts looking for fares, but unfortunately, as even Americans have seen, sexual harassment continues to beset formal public transit.

As Africa continues to urbanize, the question of how governments can best respond to the influx of people still remains. Paratransit helps answer part of that question, but in doing so, raises new questions of its own. How can policymakers ensure that paratransit continues to reduce inequality without reaffirming it? The answers to this question, in turn, raise more questions. The cycle continues, but for the time being, paratransit serves an important role in the African city—a role that will not disappear overnight. Policymakers must recognize it and respond to it. If they do not, more questions—questions without answers—will certainly emerge.