To limit encounters with high levels of toxic gases, coal miners established a practice of bringing canaries into the mines. The birds’ distress, and often deaths, cautioned the miners: if they did not act quickly, their lives were at risk. Consequently, “miner’s canary” became synonymous with an early warning of imminent danger or harm.

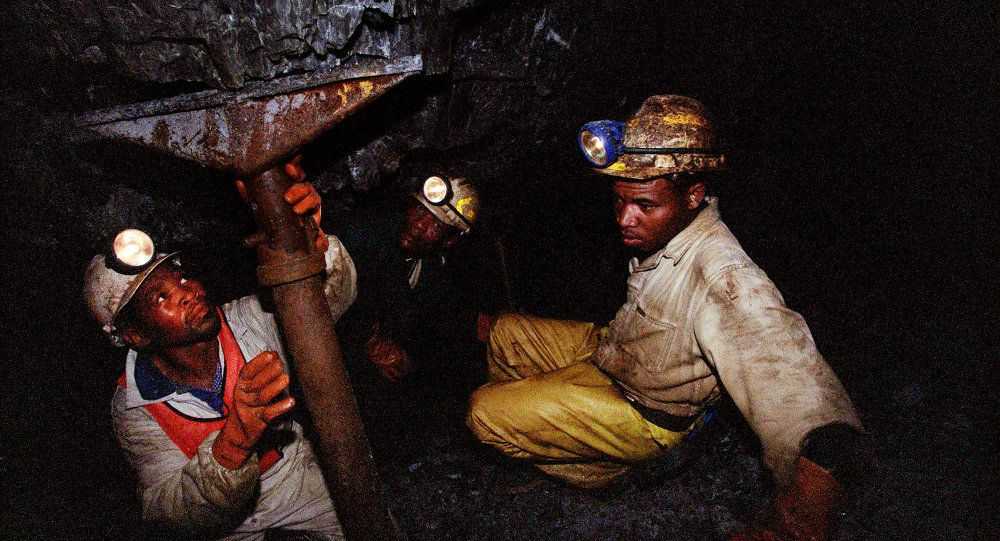

Across Africa, miners have become the miner’s canary.

When it Rains, it Pours

“I have been sitting here for twenty-six days, every day, from morning to evening. We are devastated, no one gives us concrete answers. Every day, we hope for good news. That’s why we come here every morning.”

Hoping was all that Mélène Bazié could do. On April 16, 2022, torrential rain left a group of eight African miners, including her husband and the father of her expected child, trapped over 500 meters deep in the Perkoa zinc mine in the Sanguié province of Burkina Faso. The flooded mine was operated by Trevali Mining Corporation, a Canadian company that oversees three “revenue-generating” mines and alleges to focus on delivering “sustainable shareholder value.” Trevali’s CEO Ricus Grimbeek offered an alternative view on hope regarding the tragedy, stating that “there’s always hope, but we have to be realistic.”

The Burkinabè government later provided the agonizing reality in a written statement: “After 66 days of searching, the eight miners who disappeared after the flooding have all been found dead.” The Burkinabè Movement for Human and Peoples’ Rights (MBDHP) argued that Trevali’s slowness with the search and rescue efforts was a reflection of their greater negligence. This argument seemed to hold up in court as two of the mining company’s executives were fined and charged with involuntary manslaughter, one with a 12-month sentence and the other with a 24-month sentence. However, both sentences were later suspended. The devastation in Burkina Faso and other nations across Africa is not only a story of death and deflection, but a cautionary tale for the world: when the line between economic inclusion and exploitation blurs, the progress we celebrate today will become the tragedies we mourn tomorrow.

Before the Storm

Africa is sought out by international mining companies with intention. The continent’s land primarily consists of crust that was created during the Precambrian era. Precambrian regions worldwide are renowned for their abundant mineral resources, including diamonds, gold, platinum-group metals, chromium, nickel, copper, zinc, iron, etc. Though Africa is the home of about 30 percent of the world’s mineral reserves, many of which are essential for the energy transition, large parts of the continent remain geologically unexplored and consequently, uncapitalized.

With time and through unprecedented foreign investment, the latter has changed. During the 1960s and 1970s, following the liberation of many African nations after centuries of colonialism, nationalism became a dominant ideal. This led to a significant number of state-owned mining enterprises in nations such as Ghana, Zambia, and Zaire (present-day Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)). Nevertheless, due to a lack of development in the industry, a trend of privatization emerged in the 1990s, resulting in the inclusion of international companies into the mining sector. For instance, Chinese investment in African mining quadrupled from 2000 (US$25.7 billion) to 2009 (US$103.4 billion), with rates from other BRIC and Western countries, specifically Canada and Australia, growing relatively as fast during the same timeframe. It is estimated that mining projects brought in US$18 billion in investment across Africa between 2015 and 2018 alone, with a higher amount projected for the present day.

As Right as Rain

Foreign investment through African mining is a recent example of Africa’s inclusion in the global economy, a phenomenon that’s far from new. Throughout history, Africans have participated in the global economy as traders, enslaved individuals, migrant workers in plantations, and peasant farmers who cultivated crops for export. However, inclusion through the mining industry has been considered to provide more benefits and autonomy to Africa than previous measures.

In fact, these investments have been regarded as sources of hope for the continent’s development. In the DRC, for example, the Sicomines deal came with an investment of US$6 billion in infrastructure advancements in exchange for China’s mining rights to a significant copper deposit. As foreign investors can capitalize on African natural resources, African nations benefit from increased annual growth rates pushing, improvements in governance, and an expanding middle class. In addition, the IMF estimates that by the end of the decade, the private sector could supply additional annual financing equal to three percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP to social and physical infrastructure. These factors contribute to a larger narrative that the globalization of extractive industries like mining is mutually beneficial for Africa and other nations, a beacon of light for the continent’s future.

Throwing Caution to the Wind

In the Central Republic of Africa (CAR), that light has stopped shining. The nation’s president, Faustin-Archange Toudéra, struck an agreement with the Wagner Group, a Russian private military company (PMC) that has been sanctioned for “committing widespread human rights abuses and extorting natural resources” in Africa, the former to fund its paramilitary activities in the Ukraine war. In this agreement, Toudéra received protection from rebel groups. In return, Wagner received contracts to mine gold across CAR. What was framed as a preventative measure against rebel uprisings led to far more violence: not to prevent coups, but competition.

In 2021, the Russian mercenaries attacked the town of Bambari and seized control of the town's artisanal gold mines. Because of Russia’s influence over CAR’s media landscape, the events of the massacre were pieced together from anonymized eyewitness reports. According to these accounts, the mercenaries began shooting at individuals with no words or explanations. One witness stated that "They were shooting us from the ground, and planes fired from the sky. So many people died, it was hard to count."

CAR officials stated that the attack was justified because it was to counteract rebels. However, a UN report provided photographic evidence revealing that a Bambari mosque was attacked “despite the known presence of civilians and without respect for the religious nature of the building” and that “no efforts were made to distinguish between civilians and fighters.” Their report confirmed that at least six killed in the mosque attack were civilians. The total amount of deaths from the massacre is unknown.

Events like the Bambari Massacre are underreported and underrecognized; the tragedy did not make international headlines, spark widespread outrage, or garner the world’s sympathy. African devastation thus seems to not be as profitable as African exploitation, and thus the world economy pushes for inclusion at any cost. Interestingly, these costs never seem to work their way up the global value chain, making it questionable whether any global industry, including mining, can come close to being mutually beneficial.

What some consider to be efficacious investments in African mining, others call extractive imperialism. The term is used to draw parallels between an original motivation for European imperial expansion into the Americas and the current state of the global mining industry. Both involve an outside nation utilizing resource-rich regions to its own benefit, converting natural resources into social and economic dominance. Financial Times investigative journalist Tom Burgis explains this parallel in the context of African mining, stating that “The multinational companies hold enormous economic and political power in post-independence African countries. In this way, there is a pretty straight line from colonial exploitation to modern exploitation.”

As with other forms of imperialism, extractive imperialism notably does not benefit the people of the countries whose resources are being extracted. The aforementioned Sicomines deal between China and the DRC was hailed as the “deal of the century” but in reality, it failed to serve the Congolese people. Amidst problems such as delays and unexpected costs, the deal became exempt from taxes until infrastructure and mining loans were repaid, meaning that the DRC will not generate significant profit from the agreement anytime in the near future. As a result, the very nature of this agreement has been criticized for having “never included any guarantee of the actual value that the Congolese population would get in exchange for the country’s main source of wealth.”

If anyone in a host country manages to benefit from extractive imperialism, it would be a handful of elites. For instance, Katanga province in the DRC licensed several international mining companies following a mining boom. Years later, a UN investigation uncovered that the nation’s leadership “transferred ownership of at least [US$5 billion] of assets from the state-mining sector to private companies under its control…with no compensation or benefit for the State treasury.” When Congolese civilians tried to protest against the fact that the Australian firm Anvil Mining was profiting immensely by under-compensating the local workforce, they were met with deadly military force resulting in the death of around 100 people, many of which were by summary execution.

This tragedy in DRC exemplifies one of the most harrowing features of extractive imperialism: its favor for small, elite groups and disservice to common people is institutionalized by local governments. In Angola, a nation that earns nearly half of its GDP through oil, an IMF Report revealed that US$32 billion (25 percent of the nation's GDP) was missing from official accounts between 2007 and 2010. Just as in the DRC, activists who publicly criticized these circumstances were sentenced to strict prison sentences in the name of preventing rebellion. When both federal governments and private corporations fail to support some of the most vulnerable African workers, the mining industry's fate is between change or calamity.

The Skies Ahead

While it’s clear that the African mining industry needs change to benefit local communities, this change could take various forms. One potential avenue for this change is regional integration, a phenomenon in which neighboring countries cooperate through shared rules and institutions. Oftentimes, regional integration is undervalued for countries with abundant resources because they tend to sell their commodities globally, not regionally. However, regional unions such as The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), have been able to create policy changes that prioritize trade openness, including standardized technical norms, streamlined customs administration procedures, and minimized clearance prerequisites.

In Africa, regional integration can help diversify economies away from relying solely on a few mineral exports. It can also provide food and energy security, create jobs to counter youth unemployment, reduce poverty, and ultimately promote communal prosperity rather than corporate profits. Advancement towards these aims can be seen with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which has “made significant progress in various areas of regional integration, especially peace and security, and free movement of goods, capital, services, and people.” As ECOWAS strives to overcome challenges and obstacles toward attaining a fully economically integrated community, its achievements thus far are a source of hope for African industries, in the western region and beyond.

In the end, no one can say for certain what the future of the African mining industry holds. But there are lessons to be learned from the flooded mine in Sanguié, the massacres in Bambari, the protests in Katanga and Angola, and the tragedies yet to be uncovered. If the world fails to take measures to support the laborers who carry it on their backs, if the songs of the miner’s canaries fall on deaf ears, no one can say they had not been warned.

Cover Photo: "African Profile. 16th Century AD." accessed via Wikimedia Commons and licensed under CC BY 2.0. Engraved gemstones from the Guy Ladrière Collection of Gems and Rings. On display in the Paris School of Jewelry Arts (May-October 2022).