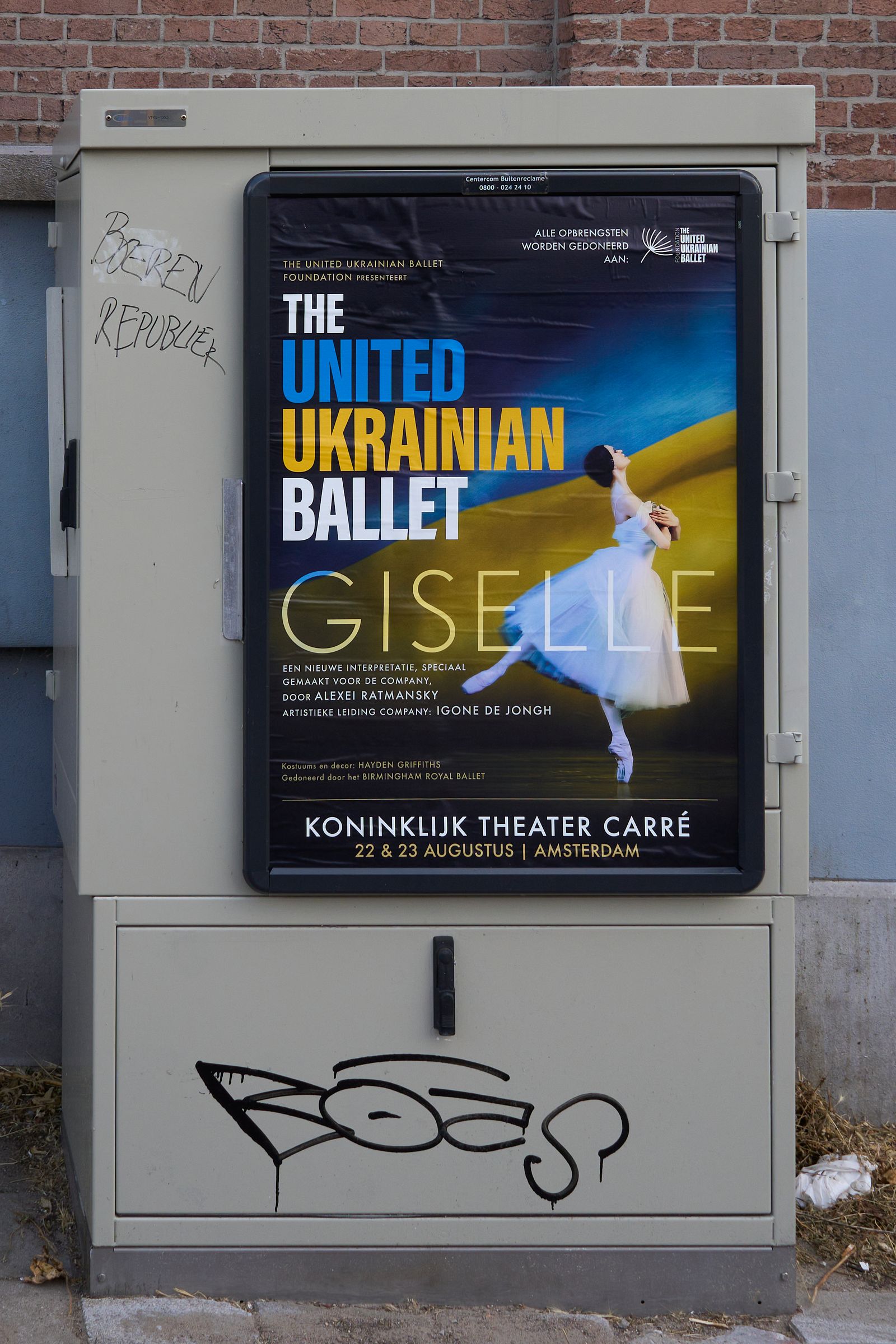

This past June, at the Segerstrom Center for Arts in Costa Mesa, California, the audience rose in a thunderous standing ovation lasting five minutes. The ballet company had just completed a rendition of Giselle, a romantic ballet about a heartbroken peasant girl, first performed in 1841. Amid the sea of white tulle, the dancers unfurled flags of bold blue and yellow—the Ukrainian flag—alongside the passionate orchestra, which played the Ukrainian National Anthem. The ballet company was the United Ukrainian Ballet, composed of refugees from many of Ukraine’s dance institutions, and choreographed by Alexei Ratmansky, who has been called “one of the greatest living ballet choreographers.”

Ratmansky’s already highly-praised work gained a renewed sense of gravity upon the reignition of the Russo-Ukrainian War. Ratmansky was raised in Kyiv, where his wife is a Ukrainian dancer. For a brief period in 2004 to 2008, he acted as the director of the Russian Bolshoi Ballet, one of the largest and most prominent ballet companies in the world. In fact, he had been working on a new ballet for the Bolshoi when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. He left for New York City immediately and postponed his new work indefinitely. Despite Ratmansky’s public withdrawal from his work for the Bolshoi and Mariinsky Theaters, Mariinsky continued to use his unfinished project of The Pharaoh’s Daughter and removed his name from the production.

The first ballet Ratmansky created since the invasion, titled Wartime Elegy, premiered in Seattle in 2022; the dancers of Pacific Northwest Ballet performed Ratmansky’s revisioning of traditional folk dances set to the music of Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov.

The statements of Ratmansky, as well as other figures in the global ballet industry, against the war and in support of Ukraine have garnered significant amounts of attention, with coverage ranging from NPR, The New York Times, The New Yorker, and The Washington Post. This extensive coverage of ballet is unlike the usual degree expected from an art form which some have predicted is dying. It even appears that the world of ballet is central to the conflict outside of warfare itself. Why, then, is ballet as a form of diplomacy so compelling in this particular moment?

History of Russian Ballet and Power

To say that ballet has been weaponized in this crisis, as described by Ukrainian dancer-turned-soldier Oleksii Potiomkin, is no overstatement. Ballet finds deep roots in Russian history and has cemented itself as an instrument of national pride. The aforementioned Bolshoi Ballet began in 1773 as a theatrical group of orphans until it was taken over by the state in 1805; foreign teachers, dancers, and choreographers like the French Marius Petipa played a role in developing the art form in St. Petersburg.

While foreigners fostered the establishment of the art form in Russia, Agrippa Vaganova emerged as one of the first and most prominent Russian voices in the field. She is credited with revolutionizing and codifying the technique of ballet in the 20th century, developing the style at the Imperial Ballet School. This particular method of teaching ballet, and its resulting distinct style, is known as the Vaganova method, and the Imperial Ballet School is known as the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet today.

Moreover, the Bolshoi Theater has been referred to as a symbol of the Russian government’s power. In the cultural sphere, distinctly Soviet art premiered there, such as the development of dramballet, a genre of ballet productions that conveyed Marxist-Leninist content as a part of the Socialist realism art movement. In the political sphere, the theater is physically close to the Kremlin and has been used for rallies and speeches. For instance, Joseph Stalin gave his infamous election speech at the Bolshoi on February 9, 1946, in which he stated that “world capitalism proceeds through crisis and the catastrophes of war.”

Ballet in a Russian Culture War

Just as in the past, many of Russia’s attempts at gaining legitimacy and soft power have found themselves in the world of ballet. On April 2, 2022, the Bolshoi Ballet announced a performance of Spartacus, with proceeds given to the “families of soldiers who died during the special military operation of the Russian Federation in Ukraine.” Spartacus is a dramballet that depicts an Italian slave rebellion in 73 BC, a production that has been described as unsubtle in its contents of suppression and struggles for power. It premiered in 1968, the same year that the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia.

Another example of how ballet is in the center of Russia’s culture war is the removal of the production Nureyev from the Bolshoi’s repertoire in 2023. Choreographed by Kirill Serebrennikov, the ballet is dedicated to the renowned dancer Rudolf Nureyev and in part depicts Nureyev’s homosexuality. Excluding this ballet was an act of complying with the recent ban on “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations.” Nureyev trained at the Vaganova Academy and defected from the USSR in 1961.

It is particularly noteworthy that many other prominent figures in ballet have actually sat opposite to the Russian state as diplomats, protestors, or emigrants. George Balanchine, born Georgi Balanchivadze, is often called the “father of American ballet,” and fittingly so: Balanchine founded the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet and developed the neoclassical ballet style which stood in aesthetic opposition to the romantic ballets of Europe. Balanchine was ethnically Georgian—his family eventually moved to the new Georgian Republic after the revolution while he trained at the Imperial Ballet School in his youth. On a tour of Western Europe, Balanchine left the Soviet Union. He later returned with his New York City Ballet as American diplomats, supported by the State Department, which wanted to push American innovation and excellence to Soviet audiences. Comparing Balanchine’s historical context and career trajectory with those of Alexei Ratmansky would breed romantic similarities. Both were and are revolutionaries of the art form, and both originated from countries struggling for independence from Russia.

Resistance and Refugees

Dancers have emigrated from Ukraine and Russia as both protestors and refugees. Olga Smirnova, who was a renowned prima ballerina at the Bolshoi, left Russia upon the invasion in 2022, saying, “I am against the war with every fiber of my being.” Despite the clarity in her resignation, the Bolshoi released a statement this past March asserting that she had been fired.

Students and company dancers, such as those who have performed at the Odesa Opera House and Theater, fled to various companies in Europe, including the Dutch National Ballet. Many of these emigrants, numbering around 60, now dance in the United Ukrainian Ballet Company, which staged a performance of Giselle in Washington D.C.’s Kennedy Center earlier this year. In 2022, the Hague in the Netherlands was a haven for the fleeing dancers of the United Ukrainian Ballet: in a dance and music conservatory, the various offices and classrooms became bedrooms. Ratmansky shared a statement of optimism amid the crisis, that “Ukraine has never been so united” in this “renaissance of politics, identity, culture, and ballet,” a sentiment which echoes through his buoyant and passionate Wartime Elegy.

The events of the last two years have shown that culture is not just a distraction from, nor victim of, politics, but that culture reflects, shapes, and breeds discourse in politics as well. Dance historian Jennifer Homans aptly noted that though physical cultural objects like libraries, monuments, and religious sites have perished in the war, it is much harder to estimate what and how many dances have been lost, because “dance is essentially stored in bodies.” But, this quality is what makes dance a powerful medium of cultural persistence and resistance. In one instance, it has become a benefit to the Mariinsky wherein Ratmansky’s choreography for The Pharaoh’s Daughter remained in the dancers’ muscle memory. In others, Ukrainian dancers can perform their art anywhere and in safety due to the oral tradition of passing on classical ballet repertoire, a knowledge not easily destroyed by violence.