A year after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that COVID-19 was a global pandemic, hope has returned in many parts of the world as the much anticipated vaccine finally rolls out. But hope for the end of the pandemic is not universal; as of February 2021, 130 countries have yet to administer a single dose of the vaccine, according to UNICEF. This leaves 2.5 billion people excluded from the global vaccination campaign, many of whom will likely wait another year or two before receiving inoculation. A recent study from the People’s Vaccine Alliance finds that nine out of 10 people in poorer countries are set to miss out on the COVID-19 vaccine in 2021.

The reasons for this delay are well known: doses are scarce, expensive, and certain vaccines require maintaining a cold chain that makes distribution in rural areas more difficult—that is, they have to remain in temperature-controlled environments through transportation and storage, without interruption, in order to preserve their quality. Recently, as the South African strain of COVID-19 has begun to spread, studies are finding that some vaccines may not be as effective against the new variant, leading to interruptions and changes even in vaccination campaigns that have already begun. For example, South Africa received one million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine in early February, only to interrupt its distribution a week later after trials suggested that the vaccine was ineffective against the South African variant. As a result, the government switched to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine halfway through the month and offered its stock of AstraZeneca vaccines to the African Union. The change in plans delayed the South African vaccination campaign by several weeks.

Beyond unavoidable delays, vaccination campaigns in low-income countries are suffering from a lack of solidarity and cooperation from the international community. Wealthy countries in Europe and North America are focusing almost exclusively on themselves and will likely have vaccinated their entire populations before many nations have even vaccinated their health workers. While some may argue that it is a government’s responsibility to address the needs of its own nation before beginning to help others, the “put on your own oxygen mask first before helping others” mentality does not apply in the context of a global pandemic.

We know far too well that pandemics don’t stop at a country’s borders, and that recovering the world’s sanitary and economic health can only be achieved through a complete global eradication of the disease in its most dangerous forms. A study from January 2021 estimates that delays in vaccination in low-income countries could cost wealthy countries at least US$4.5 trillion in lost income this year, primarily because their economies depend on international supply chains that will likely include unvaccinated countries. The threat of more potent COVID-19 variants also remains a possibility as populations remain unvaccinated. The emergence of new variants could risk a worldwide failure at containing the virus if vaccinated populations are not protected against new strains. “With a fast-moving pandemic, no one is safe, unless everyone is safe,” affirms the WHO as it urges for international cooperation. In the race against a global pandemic, “nobody wins the race until everyone wins.”

Vaccine Nationalism in Wealthy Nations Hindering Global Vaccination Goals

Inevitably, what high- and middle-income countries do now to ensure the equitable distribution of vaccines worldwide will determine the future of the pandemic and shape the dynamics of global health diplomacy in the long-term. Wealthy nations that have traditionally played an important role in the global health community are failing to meet the expectations of other nations, and international cooperation has stagnated as a result. The hoarding of scarce vaccine resources has been described as ‘vaccine nationalism’ for its self-centered disregard for the interests of the broader global population.

As a result, the inequity of global vaccination is astounding: although rich nations represent only 14 percent of the world’s population, they have bought 53 percent of all doses of the most promising vaccines so far. Out of uncertainty around which particular vaccine would end up being approved, countries like Canada, Britain, and the United States claimed doses from a number of candidate vaccines, adding up to enough doses to vaccinate their countries between four and six times over.

Since pharmaceutical goods are private goods, such inequity was to be expected. If capital determines who can access vaccines first, then countries with more capital will have priority in claiming vaccine supplies. In the United States, federal financial support for the research, development, and manufacturing of vaccines was key to the process’ rapidity, but it came with the condition that Americans would get access first. Before the vaccines had even been approved, wealthy countries had made bilateral pre-purchase agreements with vaccine developers, resulting in both a global vaccine scarcity and a bidding war that has made prices soar. Less wealthy countries cannot easily compete in this hypercompetitive vaccine market.

Vaccine nationalism and hoarding will likely prevent transnational initiatives, such as the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) initiative, from reaching their distribution goals. COVAX was created in collaboration with the WHO to pool funds and vaccine supplies from wealthy nations, with the goal of supplying vaccines to 20 percent of the world’s population by the end of 2021. However, the program has been struggling due to a lack of funds and supplies. In addition, it is grappling with the difficulty of making contractual arrangements with vaccine manufacturers who generally favor the bilateral deals they can make with wealthy nations. The challenges faced by COVAX are exacerbated by the lack of cooperation from nations and companies who continue to prioritize bilateral deals, driving up prices and pushing other nations to the back of the queue. The Director General of the WHO, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has recently warned that wealthy nations’ “me-first” approach has brought the world “on the brink of a catastrophic moral failure,” the price of which “will be paid with lives and livelihoods in the world’s poorest countries.”

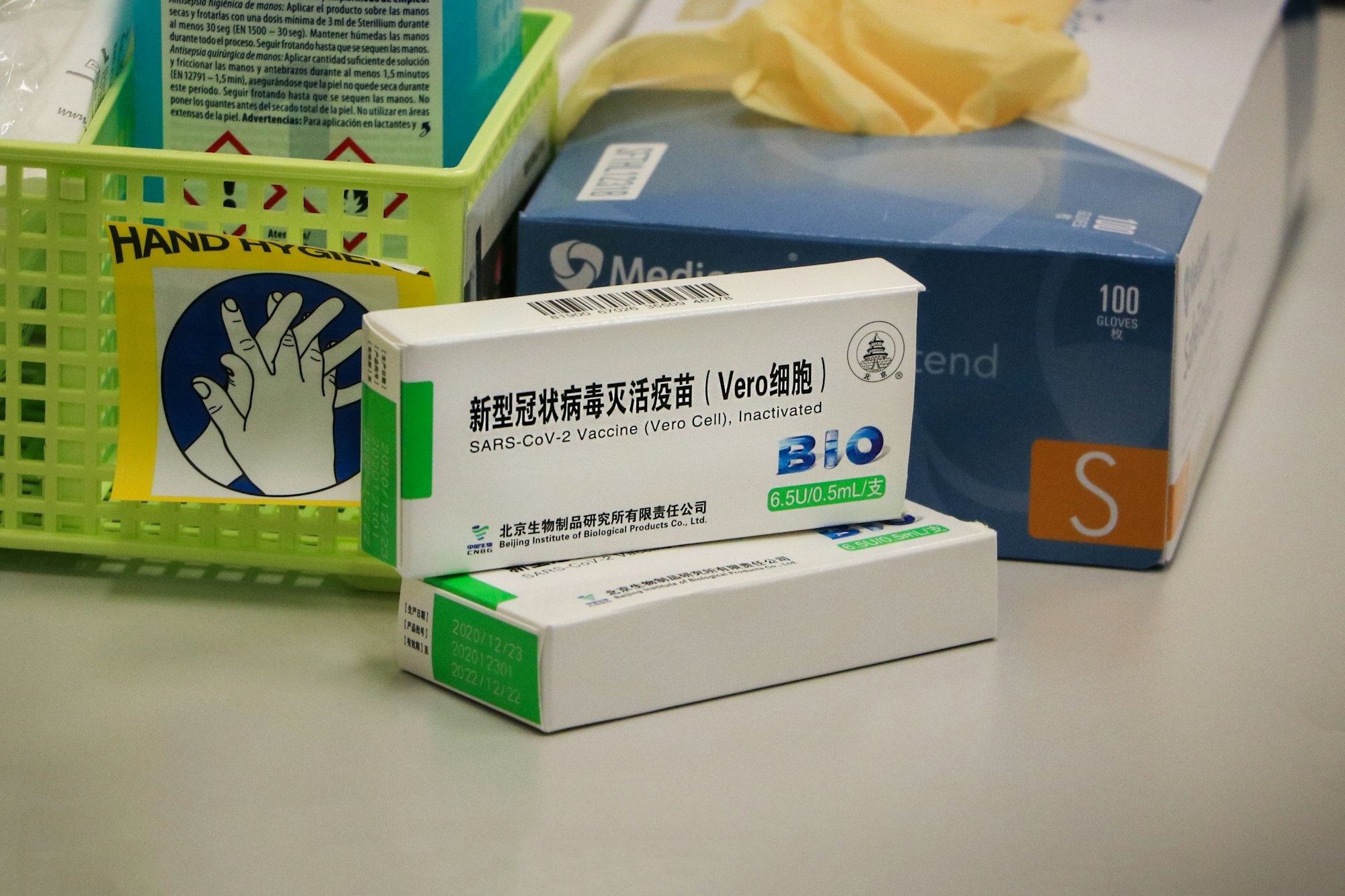

As of now, the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines have already sold 96 percent and 100 percent, respectively, of their doses to rich countries. Prospects are looking better for AstraZeneca, which has announced that 64 percent of its vaccine supplies will go to poorer countries. But the consequences of vaccine nationalism—namely, limited vaccine supplies, soaring prices, and lack of coordination—have forced low- and middle-income countries to consider using vaccines that have not yet been thoroughly reviewed and approved by the WHO, such as the Chinese Sinovac and Russian Sputnik vaccines, of which 100 percent and 99.7 percent of supplies are intended to go to poorer or developing countries. China, Russia, and other middle-income countries are promising countries in need what wealthy nations have failed to offer: a chance at affordable, equitable, and rapid vaccination.

Filling the Void: Middle-Income Countries Stepping Up to the Challenge

To counter the global inefficiency and lack of solidarity that is threatening the management of the pandemic, homegrown vaccines and local manufacturing in middle-income countries is beginning to look like the best option for low-income countries, who have abandoned the idea of receiving support from their traditional allies. For example, Argentina found itself without access to any vaccine by the end of 2020, so its government turned to Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine before any significant data about clinical trials was made public. Countries are so desperate to end the pandemic that they have been forced to treat the potential safety and efficacy of vaccines they purchase as a secondary concern. As such, middle-income countries are using vaccines as a geopolitical tool to boost strategic or commercial interests. For example, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has been donating Chinese-made vaccines to its allies while vaccinating its own population at record speed. Countries like the Seychelles and Egypt have received 50,000 doses each from the UAE, though not without some concern on behalf of those who do not trust the Chinese vaccine.

To delve more deeply into the geopolitical ramifications of vaccine diplomacy, three distinct case studies come to mind: the case of China, whose vaccine diplomacy strategies are intended to bolster its diplomatic ties abroad; India, whose Serum Institute has revolutionized the production of AstraZeneca vaccines and increased the production by millions; and, finally, Cuba, whose homegrown vaccine holds the potential for ending the greatest domestic economic crisis that the country has seen in decades.

China: Bolstering Diplomatic Ties

At least 24 countries to date have signed contracts with China to receive its Sinovac vaccine. While the Chinese vaccine is not necessarily a first choice for governments who are seeking to vaccinate their populations, it is often the only accessible option for low-income countries. The Chinese vaccine offers two major advantages. First, it will be offered at a much lower price or even for free to countries that cannot afford the American or European vaccines. Second, the Sinovac doses are much easier to transport and only require refrigeration, making it optimal for countries with weaker health and road infrastructures.

By offering vaccine doses to neighboring countries and courting regions of the world that have traditionally relied on the United States’ support, China aspires to bolster diplomatic ties and establish a budding role in the global health community. The idea, according to Dania Thafer, executive director of a Washington-based think tank, is that “instead of securing a country by sending troops, [China] can secure the country by saving lives, by saving their economy, by helping with their vaccination.”

Among its neighbors, China is using vaccination support as a strategic investment to support its Belt and Road Initiative—an infrastructure and development project that would stretch from East Asia to Europe. Beyond the near region, China has ambitions to distribute vaccines in Latin America, where it is already competing for influence with the United States through multibillion-dollar investment and infrastructure deals. Since the early months of the pandemic, it has been sending shipments of medical supplies to Latin American countries, filling a void left by the US administration which, under former President Donald Trump, had failed to support its regional partners. In total, the countries that have purchased Chinese vaccines range from Indonesia and the Philippines to Algeria, Ukraine, Turkey, and even Brazil, which has been manufacturing the Chinese vaccine in its own production centers for the Latin American region. Through its global vaccination campaign, China is on a mission to bolster diplomatic ties with middle- and low-income countries and to establish itself as an important actor in the global health community.

India: Manufacturing Vaccines at a Record Speed

The case of India is different but nonetheless important to the story of global vaccination, as the country is proving to be extremely influential in the large-scale manufacturing of vaccine supplies for low-income countries. Indian pharmaceutical companies have not invented any vaccine of their own—instead, they obtained approval from AstraZeneca to manufacture their vaccine in the largest vaccine factory in the world, the Serum Institute. The Institute is currently manufacturing millions of doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine a day, and has pledged to deliver 200 million doses to COVAX. That is 20 times more doses than China has recently pledged to deliver. With a production rate of 70 million doses a month, which should increase to 100 million by the end of March, the Institute aims to send out 2 billion doses by the end of 2021.

Indian production of the AstraZeneca vaccine is another clear example of non-Western countries stepping up to the challenges of global vaccination in the absence of real Western involvement. India has been sending doses free of charge to its neighbors, such as Nepal, Bangladesh, Myanmar, the Maldives, Sri Lanka, the Seychelles, and Afghanistan. To others, including COVAX, the Institute will sell doses at the low price of US$3 to US$5—essentially making no profit on the sale of the vaccines to low-income countries. For comparison, the cost of other vaccines averages around US$15, and Pfizer makes about an 80 percent profit margin on the sale of vaccines to high-income countries. On February 15, 2021, the WHO granted emergency use listing to the vaccine produced by the Institute, which will allow countries to expedite their regulatory approval process and begin importing and administering the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible.

Of course, there are also diplomatic considerations to the Indian vaccine strategy. Constantino Xavier from the Centre for Social and Economic Progress in New Delhi asserts that “the vaccine push bolsters India’s credibility as a reliable crisis-responder and solutions provider to these neighboring countries.” In countries like Nepal, the vaccine is an opportunity to normalize ties between governments that were facing increasingly tense political relations. But, beyond the diplomatic advantages of the vaccine-sharing strategy, there is a real desire for solidarity and for ending the disastrous pandemic globally as soon as possible. This ambition contrasts slightly with that of China, which has branded its assistance mainly as fulfilling diplomatic needs rather than a purely altruistic intervention.

Cuba: Encouraging Homegrown Vaccines

Finally, the case of Cuba depicts the promising efforts of a smaller nation that is counting on its own homegrown vaccine to combat the lack of global vaccine supplies in a highly competitive market. As of February 17, 2021, Cuba is moving into “Phase 3” trials of a vaccine that was invented on the island. First, Cuba hopes to vaccinate its full population. Second, it plans to give away doses to poorer countries, in keeping with its custom of donating medicine and sending doctors abroad to help address public health crises while strengthening its diplomatic ties. Finally, the Cuban government expects to offer its vaccine to travelers who visit the island, which would boost the country’s tourism sector. While the government depicts this initiative as primarily intended to increase health, it also admits that the economic boost would be more than welcome at a time when the country is facing its worst economic crisis since the 1990s.

Once again, Cuba’s vaccination strategy exemplifies the self-reliance and ingenuity that low- and middle-income countries have had to develop during this pandemic. Because it could not rely on Western support (for reasons that also go beyond those mentioned above, such as US sanctions and embargo), Cuba balanced self-sufficiency with international solidarity. The notable trend that characterizes all three cases studies above is that nationalist ambitions and economic interests can go hand-in-hand with international solidarity, and that countries that cooperate with those in need may benefit both economically and diplomatically from their role in combatting the pandemic.

China, India, and Cuba are prime examples of combining self-interest and international solidarity. While vaccinating their own populations with home-made vaccines, they are also sharing the vaccine with those who do not have the same manufacturing capabilities. This approach differs from that of wealthier countries mainly in terms of timing: for wealthy nations, vaccinating their own populations has been the priority so far, and the fate of other countries has been of secondary concern. Most likely, wealthy nations will begin to engage more with the international community as their own vaccinations reach a satisfactory stride. On the other hand, middle-income countries like China, India, and Cuba, have realized that overcoming the pandemic is a global effort, not a national endeavor. They understand that they will gain more from international cooperation than from cutting the line and waiting for other countries to figure it out on their own.

Global Implications of Vaccine Diplomacy

The strategies depicted above, however, have some limitations. Citizens are often less eager than their governments to accept a Chinese or Russian inoculation: in a study by YouGov of roughly 19,000 people in 17 countries, survey respondents were most distrustful of COVID-19 vaccines that were developed in China and Russia. To the question, “Would you tend to think more positively or negatively about a COVID-19 vaccine if you saw that it was developed in each of the following countries?,” vaccines developed in China and Russia received negative scores of -19 and -16, respectively. In contrast, vaccines developed in Germany and Canada received scores of +35 and +29, respectively.

These scores can likely be explained by the uncertainty and lack of disclosure surrounding the Chinese vaccine. Data about the vaccine’s safety and efficacy is difficult to find and has changed since the first announcement by the Chinese government. For example, while officials in Turkey publicize a 91 percent efficacy rate of the vaccine, the number changes to 68 percent in Indonesia, and 78 in Brazil. There seems to be no agreement on the actual efficacy rate of the vaccine so far. Secrecy around the Chinese vaccine and general doubts concerning the production of vaccines in middle-income, non-democratic countries may be contributing to a rise in vaccine hesitancy in countries that are already expected to struggle to reach herd immunity.

In addition, countries like India and China have massive populations themselves that vaccinations as well. In China, for example, a recent outbreak placed an unexpected burden on the health system and brought greater urgency to vaccinate its population, delaying the shipment of vaccine doses that had been promised to other countries. In late March 2021, India placed a temporary hold on exports due to rising domestic cases and domestic demand for vaccines, causing delayed shipments to dozens of countries as well. Huge quantities of vaccines will be needed just to vaccinate India’s vulnerable populations, which amounts to around 200 million people. As the speed at which vaccinations are given out increases, the government may face increasing backlash if it is exporting supplies that its own population needs.

Despite these challenges, the case studies of China, India, and Cuba demonstrate a shift in international global health dynamics, in which low- and middle- income countries are relying less on the United States and Europe and more on their neighbors, on regional powers, and on similarly wealthy nations for help. While there is reason to believe that the Chinese vaccines may not be entirely effective or up to the scientific standards of Pfizer or Moderna, the fact remains that Sinovac and Sinopharm are among the few manufacturers that have prioritized the needs of low-income countries over their own financial interests.

While Western manufacturers were making bilateral agreements with wealthy nations, manufacturers in India, China, and Cuba, among others, were considering how best to combine their own immunization ambitions with responding to the needs of other countries around the world. These countries are not cooperating for purely selfless reasons—on the contrary, they have realized that the Western failure to step up to the international vaccination challenge was the perfect opportunity for them to establish their place as leaders in the global health community. Most importantly, middle-income countries recognize that ending the pandemic will require international cooperation rather than isolationism—and that the pandemic won’t be over anywhere until it’s over everywhere.