Since the first steps on the Moon in the 20th century, space has been an exciting frontier for all of mankind. In the past, space expeditions were primarily conducted by the government agencies of a handful of nations, with an increasing number of countries creating their own space agencies and technologies. However, the past few years have seen the rise of private space corporations like SpaceX and Blue Origin, promising private citizens greater access to this frontier. Cooperation between public and private institutions has the potential to make space exploration and space tourism more feasible and affordable, which in turn boosts economic growth and encourages research in space technology. On the other hand, there are concerns about the construction of weapons and surveillance tools in space as a result of this increased accessibility. A related and often overlooked point is the necessity of planetary protection as the space domain continues to be explored.

When space exploration was dominated by public institutions, most space agencies obeyed anti-contamination procedures set by the "soft laws'' in the Outer Space Treaty (OST) and the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) Planetary Protection Policy. However, the remarkable growth of private space exploration and development has raised concerns about the future of planetary protection in the absence of enforceable laws. International cooperation will be crucial to preserving the environment of Earth and outer space, with the UN perhaps best suited to spearhead this effort.

What is Planetary Protection and Why Does it Matter?

Planetary protection is defined as protecting extraterrestrial environments from Earth-based contamination (forward contamination), as well as protecting Earth from extraterrestrial contamination (backward contamination). Satellites and space rovers are often sterilized at high temperatures before being launched to ensure that no Earth-based organisms are accidentally introduced into outer space. It is akin to protecting ecosystems on Earth from invasive species. For example, when entering protected waterways, boats are encouraged to flush out their ballast water and rinse external surfaces to prevent non-native species from infiltrating the native ecosystem.

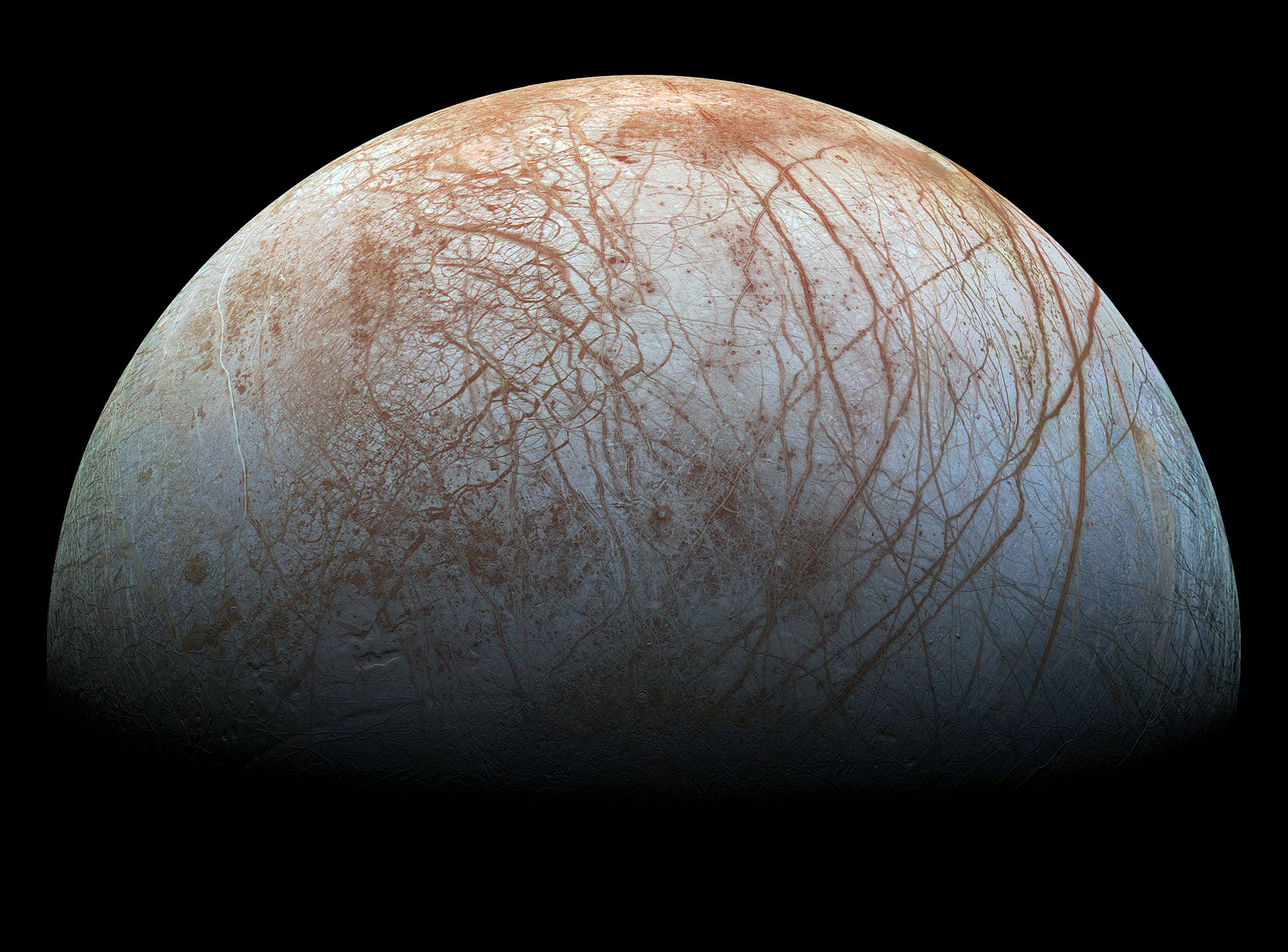

While outer space often seems remote and sterile from our perspective on Earth, each extraterrestrial environment is unique, and some could even be hospitable to life. Scientists theorize that Mars once possessed liquid water, though only ice exists at its poles now. Studies of Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa have suggested that there may be underground liquid oceans on these moons. Searches for life outside of Earth are dependent on the preservation of extraterrestrial environments, since contamination from Earth-based organisms or even organic compounds could lead to faulty data and unreliable conclusions.

Contamination can also work in the opposite direction: if life is discovered on another planet or moon, bringing them back to Earth without proper sterilization processes could result in disastrous consequences. The analogy of invasive species illustrates the importance of planetary protection—if contamination between populations on Earth can wreak havoc on our ecosystems, it is reasonable to assume that life from other planets could do the same. If life exists on other planets, it has likely evolved differently from life on Earth, making it extremely unpredictable to study and difficult to control if introduced to Earth’s environment.

Current International Policies and “Soft Laws”

Currently, the main legal framework for all activities in space is the Outer Space Treaty, a 50 year old agreement signed by all major space-faring countries under the auspices of the United Nations. Article IX of the OST states that nations have an obligation to prevent backward contamination, but there is no clause on forward contamination. The Moon Treaty, an extension of the OST, includes an active obligation to prevent both forward and backward contamination, but with India as the only major space-faring signatory, it fails to carry significant international sway.

In terms of extending the legal framework for planetary protection to private space exploration companies, Article VI of the OST states that governments are responsible for the activities of both governmental and non-governmental entities within their borders in space. Thus, national governments are obligated to ensure that both their public and private space-faring organizations are in compliance with the planetary protection provisions of the OST. However, few governments have passed domestic legislation with more specific planetary protection measures, which leaves a gap between the general OST clause and actual enforcement of anti-contamination procedures.

One significant non-governmental organization that works closely with the UN’s Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) is the Committee on Space Research. COSPAR is a body made up of representatives from national and international scientific institutions that conducts and promotes collaboration on planetary protection research. COSPAR periodically publishes detailed recommendations for planetary protection laws and procedures, forming a body of “soft law” that can inform official legislation. While COSPAR’s policies are not necessarily enforceable, the advantage of “soft law” is that it can adapt more easily to new research in planetary protection and the rapidly changing private and public space sector, as it largely lacks the bureaucratic burden of institutions such as the OST, which must undergo many rounds of voting and revision before ratifying new standards.

One proposed solution for better enforcing planetary protection law lies in increasing domestic national legislation. However, it is difficult to ensure that each nation is following the best practices for planetary protection, and it is similarly difficult for international organizations to influence individual nations to adopt standardized policies. Another solution may be to expand awareness of COSPAR’s recommendations and educate space-faring nations and companies on these policies, but it is hard to predict how closely they will be followed without legal enforcement. This reality suggests that the most promising solution for global cooperation in planetary protection is a framework that is both enforceable and malleable. A structure that satisfies both of these conditions could manifest in a board of planetary protection “ambassadors” who are selected from each country by UNOOSA and consult with COSPAR. These officers could help educate domestic space agencies and legislatures about planetary protection, which could in turn encourage tailored domestic legislation within those countries while still being under the guidance of the UN, helping to keep planetary protection law coherent across borders. During this crucial transition to the new space age, all space explorers, public and private, will need to work together to protect not just the Earth, but the broader extraterrestrial environment.

Cover Photo: Long exposure of the launch and landing of the SpaceX CRS-9 Falcon 9 rocket. Photo by SpaceX, licensed under CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.