Hidden behind years of societal and governmental oppression, the current humanitarian crisis in the Dominican Republic combines racism, US imperialism, and the demands of the global sugar market. While the world grapples with a racial reckoning and a historic pandemic, the violent history of the bateyes remains absent from discourse. A deeper look into the crisis that binds the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and the United States together provides the key to awareness and a first step towards reconciliation.

The Batey System

A batey is a community built around the sprawling green stalks of a sugar mill. Although located in rural settings, they resemble what many know as a shanty town, a slum, or a ghetto—in stark contrast to the greenery and bright beaches associated with the Dominican Republic. In effect, these settlements around the Dominican Republic (DR) house between 200,000 to 1 million people who have little to no access to water, electricity, education, or legal counsel, especially pertaining to their labor rights. This juxtaposition of extreme poverty and Caribbean paradise traces back to the nation’s authoritarianism in the twentieth century. During his 30 years of rule from 1931 to 1961, dictator Rafael Trujillo created the batey system, in which workers from Haiti would be brought to work during the seasonal sugar-cane cutting harvest, minimizing the cost of labor. The system was intended to satisfy the growing need for quick and cheap sugar to export through what the Latin American Research Review describes as “a government-managed system of semi coerced exploitation.”

Sources and Causes of Emigration from Haiti

While Trujillo ruled the Dominican Republic, Haiti suffered from instability and an economic crisis. The country gained its independence from France in 1824, but at a large price: Haiti had to pay its former colonizer an indemnity, which left the new nation indebted and vulnerable to foreign influence. The effects of this vulnerability worsened in the early years of the 20th century as Germany heightened its activity and economic influence in Haiti. Instability increased between 1911 and 1915 when seven presidents were assassinated, prompting the United States to take action. The United States occupied Haiti from 1915-1934, an interventionist move geared towards preserving a diplomatic and military stronghold in the region. Racial segregation, peasant uprisings, strikes, press censorship, and labor abuses followed US intervention until American withdrawal in 1934 in accordance with Woodrow Wilson’s Good Neighbor Policy. During this complex geopolitical and economic crisis, thousands of Haitian migrants left to work in the Dominican sugar industry, prompted by promises of work, Trujillo’s increase of labor demand, and Haiti's capitalization on emigration. During joint American-Haitian rule, recruiting permits and emigration fees for workers sent to the DR made up the Haitian government’s largest internal source of revenue. Haitians looking to improve their conditions were funneled into the sugar plantation labor system at the benefit of both countries’ economies, or seemingly so on the macroeconomic level. Back in the DR, Trujillo’s economic policies eventually led to him possessing 60 percent of the DR’s sugar, tobacco, and other assets, heightening economic inequality and plunging many Dominicans into poverty.

Racial Violence

The economic history of Haiti and the DR is crucial in understanding the racism, animosity, and poverty that the bateyes face. Not only was Trujillo instrumental in the economic downturn of his country, but he also served to heighten xenophobia and racism. Supposedly sparked by Dominican complaints over cattle rustling and theft, the Parsley Massacre in 1937 followed Trujillo’s aim to “whiten” the DR. For five to eight days, the military drove out or killed Haitian workers that had settled for work at the border, using a twisted linguistic tactic to differentiate Haitians from “purer” Dominicans. The word for parsley in Spanish is “perejil,” which involves a distinct pronunciation of the j and r sounds that were difficult to emulate in the French language of Haiti. This ethnolinguistic massacre left between 9,000 and 30,000 dead, including descendants of Haitian immigrants and darker-skinned Dominicans.

Antihaitianismo

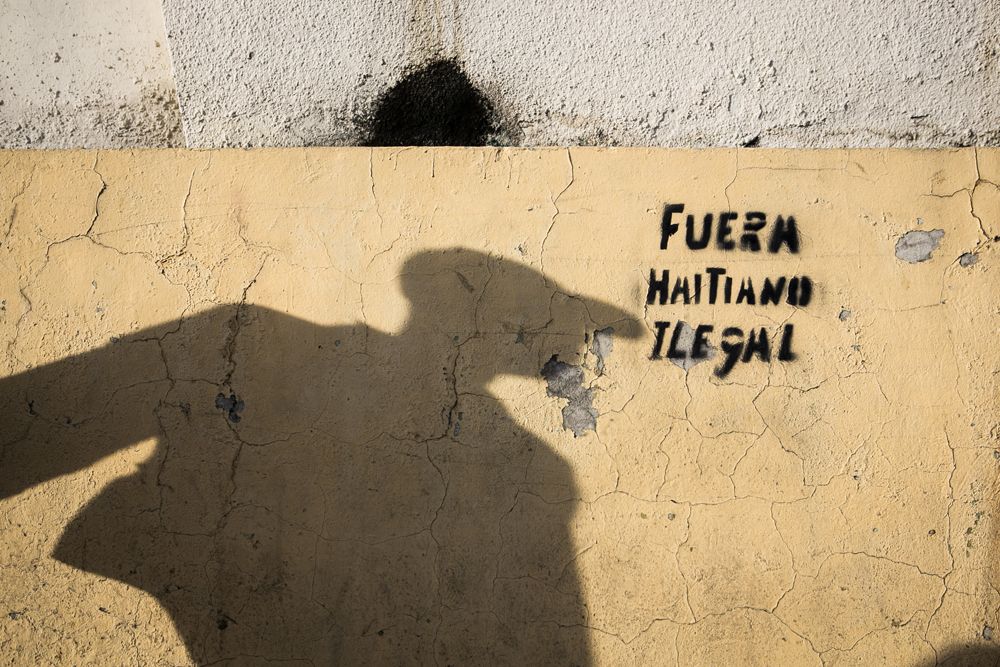

While the Dominican economy eventually moved away from sugar cane and toward mining, manufacturing, and tourism, racism in the DR persisted after Trujillo, coming to be known as antihaitianismo, or anti-Haitianism. Under recent President Danilo Medina, this anti-Haitian sentiment still lingers as seen in citizenship law changes. In 2013, a court ruling stripped citizenship from Dominican-born children of undocumented parents for the past century. This was a widely contested move that led to a slight amendment in 2014 for Dominicans of Haitian descent. In regards to the bateyes, this amendment did nothing; many of the bateyes’ occupants have no documentation, be it a birth certificate or any other proof of citizenship, making the reclamation of citizenship impossible. The time and financial toll of registration and citizenship reclamation deepened inaccessibility to the process. The law received strong backlash from activists and organizations which saw it as a means of revealing, persecuting, and deporting undocumented Haitian immigrants and their descendants, but to no avail. The policy rendered at least 210,000 people stateless in contrast with the government’s official report of no more than 13,000. Repatriation and forced deportation still occur, with at least 10,000 people having been deported back to Haiti by the end of 2015.

Another troubling element of antihaitianismo is its prevalence within Dominican culture. Important journalists, authors, and politicians highlight the wide-spread racist and aggressive anti-Haitian culture that includes direct personal attacks, historical manipulation, and policies aimed at keeping Haitians in the lowest social strata. Textbooks of Dominican history present a biased, and often false, account of the history between the two nations of Hispaniola with Haiti often presented as an aggressor. Undocumented children are barred from getting an education past the eighth grade and Dominicans of Haitian descent must carry with them a pass called a cedula, which is identification required to access a range of political and social rights, but is impossible to receive without a birth certificate. This racist and nationalist animosity also leads to violent, personal attacks. In one such instance reported by the Economist, a Haitian bears the mark of a Dominican’s machete, inflicted in an argument over debt.

Repercussions of COVID-19 and Initiatives for Change

During the COVID-19 epidemic, the shutting down of small businesses did not spare the batey and Haitian-Dominican communities. Government aid was only given to citizens, thereby excluding many in these communities. In a quote to Telemundo 47, a Dominican worker named Anilda states that “el hambre está desesperando a las personas,” the hunger is waking up the people. In the midst of economic recession caused by the pandemic, these communities have additional fears about access to health care and basic resources. As of October 7, 2020, the DR had 116,148 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 2,159 confirmed deaths in a population of about 10.8 million people.

Back in the bateyes, few are talking about the impact of the COVID-19 crisis due to a lack of awareness across the DR. This makes humanitarian efforts difficult to pursue. Nonetheless, organizations, such as the Batey Relief Alliance, the Asociación Scalabriniana al Servicio de la Movilidad Humana (ASCALA), and the Batey Foundation, work to promote development, sustainability, and education in these severely impoverished and disadvantaged communities through hunger relief, labor and female empowerment, legal aid, and entrepreneurship training. All three of these organizations push for internal initiatives, promoting long-term sustainability rather than only short-term gain from foreign volunteers and donations.

Awareness and action are necessary to solve this issue, which hits on immigration, forced repatriation, racism, and previous US intervention. Casting light on this culmination of a conflict-heavy history and the dark side of global market competition works to ensure that the workers of the bateyes are recognized and afforded the human rights they are currently lacking. It is far past time that the United States stares directly at the consequences of its involvement in Latin America and works to promote anti-discriminatory behavior abroad as much as it is seeking to do so within its borders. The United States’ recognition of past racist international policy, reparation, and aid will go far in improving the lives of the bateyes’ stateless.

Cover photo: "Entre Bateyes" by Fran Afonso is licensed under CC BY 2.0.