While much of the focus on international climate action has focused on the 2015 Paris Climate Accords, countries such as the United States, European Union (EU) member nations, China, and Russia have all been attempting to cement themselves as leaders of multilateral climate policy. On July 14, 2021, the European Union took a step in pronouncing their approach to climate change by proposing the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which would tax imports based on the environmental impact of their products such as aluminum, steel, and cement, which comprise a bulk of emission levels. In their announcement of the CBAM, the EU tied this new policy proposal to their existing goal of climate neutrality by 2030. In the few months since the EU declared its intention to enact the CBAM, there has been a wave of backlash and outrage from nations who trade with the EU, particularly from Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (the BRICS nations). As the EU attempts to assert itself as the global leader in addressing climate change, the question remains whether the financial implications of their policies, and the policies of other nations positioning themselves to take a more assertive stance on climate change, might hinder EU policy goals.

Who Pays the Price?

Based on current export and import activity, Russia, China, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and Ukraine are currently facing the steepest penalties under the CBAM (in order of dollar amount). In response to a 2019 European carbon border tax, China previously argued that the mandate would reduce Chinese exports and diminish China’s ability to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. The 2021 CBAM is considerably more strict than the 2019 European tax based on the scope of goods that it targets. This begs the question as to whether China will threaten countries who comply with financial retaliation in order to avoid more restrictive policies. To that end, China has accused the EU’s CBAM proposal of violating World Trade Organization (WTO) principles. In response, EU officials stated that the CBAM was written specifically to be compliant with WTO rules. The invocation of the WTO, a multilateral organization, by Chinese government officials suggests that they are making a case against the EU’s institutional legitimacy. While China’s opposition to the CBAM is likely motivated by the overwhelmingly negative financial consequences they would face in its implementation, they are voicing their objections through the lens of multilateral norms. The obfuscation of China’s true intentions, namely preserving economic growth, by targeting institutional legitimacy could give other nations the justification that they need to cut exports to the EU, circumvent the CBAM, or potentially pressuring the EU into rescinding the mandate.

Unlike China, Russia has framed their arguments against the CBAM by claiming that the EU is acting in bad faith. Trade relations between the EU and Russia have been tense for decades since the Cold War and have been exacerbated by EU sanctions implemented following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. Russian government officials and business owners alike describe the CBAM as the EU’s way of recouping financial losses that they experienced due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Laurent Bardon, Head of the Trade and Economic Section at the EU delegation to Russia, responded to these allegations by criticizing Russia’s lack of action on climate change. Indeed, Russia has regarded the effects of climate change as a potential opportunity to bolster their economic strength by claiming more territory in the Arctic Circle which will become increasingly available as polar ice caps melt. With such divergent views on climate and global issues at large, the CBAM threatens to drive yet another wedge in the already-contentious EU-Russia relationship.

One key reason why Russia’s publicly-stated objections to the CBAM differ from China’s is the long history between the EU and Russia. While the EU and China have managed to maintain substantial productive economic ties, the EU and Russia have had a much more antagonistic relationship rooted in ideological differences and geographic proximity, heightening mutual threat perception. The EU’s attempt to assert itself on the global stage through the CBAM may thus be felt much more strongly for Russia, the most financially affected country. From the EU’s perspective, the duality of these criticisms means that they must defend the CBAM as a globally-beneficial policy that is consistent with WTO rules and does not target any one particular nation.

The EU currently has a domestic policy known as the Emissions Trading System (ETS), which limits greenhouse gas emission to a set maximum amount and allows companies under the framework to buy and sell the rights to emit certain amounts of greenhouse gases. As such, the ETS’ existence means that the CBAM represents the EU’s attempt to make international companies play by the same rules that already regulate domestic manufacturers across Europe. From an environmental standpoint, the CBAM represents the logical next step forward in containing emissions. While the ETS’ jurisdiction is limited to EU member nations, the CBAM allows the EU to de facto regulate the carbon emissions produced by corporations around the world. The combination of the CBAM and the ETS thus demonstrate the EU’s commitment to decreasing carbon emissions through an economic regulation process.

Will Other Countries Follow?

At the July 2021 G20 Climate and Energy Ministers Meeting, US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry said that the United States was not considering implementing its own version of the CBAM due to its pursuit of multilateral relationships. His comments came four months after he called a US version of the CBAM a “last resort,” in March 2021. Kerry’s view, however, is not representative of all US lawmakers. Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR), along with other Senate Democrats, have proposed a polluter import fee that resembles the CBAM. Yet any action to implement a potential CBAM in the legislative branch would be inherently constrained by partisan politics and gridlock. The executive branch’s hesitancy to implement their own CBAM seems motivated by its commitment to a different approach to climate change—fostering multilateral relationships in an effort to encourage a coordinated approach.

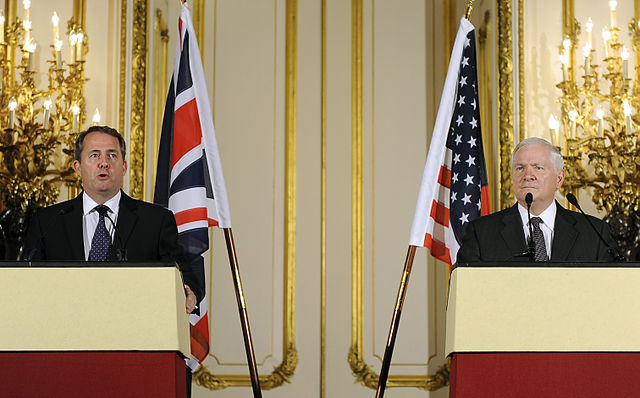

In the United Kingdom, former Secretary of State for International Trade, Liam Fox, has been the leading voice in favor of a carbon border tax. Fox’s outspoken support led the Department for Business, Energy, Innovation, and Skills (BEIS) to put out a statement in May 2021 indicating that they were considering the idea of implementing a carbon border tax. However the actual passage and implementation of a UK carbon border tax seems unlikely due to its effects on the British relationship with Australia and other Indo-Pacific trading partners.

While neither the United States nor the United Kingdom are likely to implement a carbon border tax in the imminent future, the EU’s CBAM proposal had a noticeable impact on the discourse surrounding such a policy in both countries. The United States, the United Kingdom, and the EU differ on their prioritization of multilateral relationships in considering global climate regulations. The EU’s gambit is that the CBAM will be successful enough in inspiring other nations to take climate action and in reducing emissions that any potential damage to international relationships will be well worth the cost. The United States seems to view multilateral relationships as a crucial tool in the fight against climate change and appears to believe the fallout from a broad carbon border tax could harm other climate efforts down the road. One example of the United States utilizing multilateralism in climate change policy is President Joe Biden’s pledge to double climate change-related foreign aid by 2024. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has specific allies that they believe would be disproportionately impacted by a carbon border tax and do not wish to risk relations with those governments. In fact, the United Kingdom recently decreased their climate change pledges to secure a trade deal with Australia, which seems consistent with their worry that a version of the CBAM would harm the long-standing relationship. While the CBAM’s environmental impacts have yet to materialize, national leaders around the world are already planning domestic and foreign policy initiatives based on its looming realization.

Conclusion

The CBAM policy is a landmark initiative due to its large financial and ecological scope as well as its significant impacts on national economies. By announcing such an ambitious policy, the EU has made their intention of being a global climate leader clear. The United States, the United Kingdom, China, and Russia all have considerably different approaches than the EU to influencing global climate policy. It is possible that the negative financial impact that the CBAM has upon the United Kingdom, China, and Russia makes them and other nations less likely to cohere with EU policies in other arenas. That possibility seems to be a powerful motivator for strong US climate policy. The CBAM certainly represents an important milestone and litmus test in determining which approach is more effective.

Cover photo: Leeuwarden, the flags of the European Union at the Stationsweg, on May 21, 2018. Photo by Michiel Verbeek, Leeuwarden, Netherlands, Image is in public domain, accessed via Wikimedia Commons.