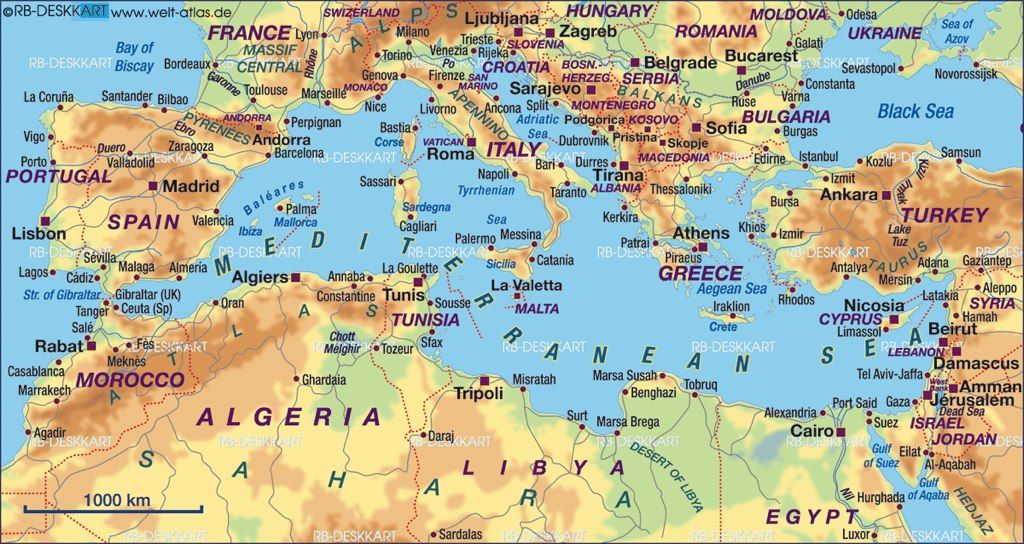

The number of asylum seekers in the European Union has skyrocketed. The current situation is reminiscent of the 2015-2016 crisis, during which 1.3 million people illegally immigrated to Europe from the Middle East, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Driven by political and economic insecurity, migrants and refugees have long departed from Tunisia, Libya, and Turkey, risking the perilous journey—nicknamed the harraga—across the Mediterranean or Balkans for a new life in Europe.

Yet, an often-overlooked aspect of the journey to the European Union is smuggling networks. Human smuggling offers a means to an end for many desperate asylum seekers and constitutes a highly lucrative business. EU efforts targeting these criminal networks are unlikely to succeed without considering both of these factors.

Tunisia’s border crisis

As Libya has increased border security over the past two years, Tunisia has become the primary departure point for illegal sea crossings. The city of Sfax, specifically, is a hub for clandestine migrants, given its proximity to the Italian coastline and outer islands. Between January and March of this year, the Tunisian National Guard intercepted 14,406 migrants in the waters outside Sfax. Furthermore, under the Tunisian legal code, these intercepted migrants are not considered lawbreakers. Many attempt the journey multiple times.

Tunisia makes for an especially likely stepping stone to Europe for sub-Saharan nationals, as most do not need a visa to travel to Tunisia. Notably, the presence of Black Africans in Tunisia is nothing new. First in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as slaves and now as low-wage laborers, students, and working professionals, the cohort has historically been a part of Tunisian society.

Yet, tensions between foreign Black nationals and Arab Tunisian citizens have been on the rise. On February 21, 2023, increasingly authoritarian President Kais Saied made a speech stoking racism and xenophobia. In it, Saied condemned the presence of Black Africans in Tunisia, designating the group as a “demographic” threat designed to turn Tunisia into “just another African country that doesn’t belong to the Arab and Islamic nations any more.” Since then, there has been an uptick in protests and violence targeting sub-Saharan Africans, including those who are long-term residents of Tunisia. Even the national government has perpetrated offenses against the group, such as abandoning asylum seekers in remote desert border areas near Algeria and Libya. The situation has certainly contributed to the flood of migrants into the European Union as former North African enclaves have turned hostile.

Human smugglers and the journey to Europe

Human smugglers are an inextricable link in the chain that takes migrants to the European Union. They operate along two major routes: one across the Mediterranean and another through the Balkans. Most migrants connect with human smugglers through social media platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook.

The sea route takes between eight and 10 hours. Migrants generally depart from Sfax, though some leave from the country’s capital, Tunis. Their destination is often Lampedusa, an Italian island located 110 miles from Sfax.

The Balkan route is longer and more expensive but generally seen as safer than the Mediterranean route. The journey involves two flights: from Tunis to Istanbul and then to Belgrade. Once on the ground, migrants travel some 140 miles to the Hungarian border. This leg of the journey is incredibly dangerous. Migrants often hide in the Radanovac forest with little access to food or water. After crossing into Hungary, some smugglers transport migrants to Austria, which is part of the no-passport Schengen Area. Once in Hungary or Austria, both EU member states, migrants apply for asylum. The recognition rate for applicants is 40 percent.

A lucrative business

The growing number of clandestine migrants is bad news for almost every actor involved. As the European Union struggles or refuses to accommodate the influx of asylum seekers, the perilous border crossing has caused hundreds of deaths and missing person accounts in 2023 alone. One group, however, seems to be benefiting from this crisis: the gangs that control Tunisia’s human smuggling networks.

Human smuggling is highly profitable. The network through the Balkans makes nearly 50 million euros (around US$54 million) annually. Migrants traveling via this route pay smugglers at least 7,000 euros (around US$7,600) and even more to get to the Schengen Area, while the Mediterranean route costs between 1,200 and 2,200 euros (around US$1,300 to US$2,400). To compare, Tunisia’s GDP per capita is approximately US$3700, substantially higher than sub-Saharan countries’ average of US$1600. Migrants, therefore, make a concerted effort to afford the smuggling cost. It is not uncommon for friends and family to pool resources to finance a single person’s travel to Europe.

European officials point to these “ruthless smugglers” as the main obstacle in solving the migrant crisis. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte stated that the goal of the recently proposed EU aid package to Tunisia is to “kill that cynical business model of the boat smuggler.” But this may prove difficult, given that Tunisia’s smuggling rings are more decentralized than neighboring Libya’s, making it harder for officials to clamp down on them.

Not everyone blames human smugglers for the current situation. Some criticize the European Union, saying that its tougher immigration policies have encouraged smugglers toward more dangerous routes. According to this line of reasoning, the EU aid package, which is tied to stringent border control, will, if implemented, result in more casualties and missing persons.

Nevertheless, states appear to be taking smuggling seriously. In 2014 and again in 2018, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) published statements directly affirming that the smuggling of migrants is one “of the world’s most shameful crimes that rob[s] people of their dignity and basic rights.” The Tunisian Interior Ministry announced that it has arrested more than 550 “organizers and intermediaries” of these criminal networks already this year, including a notorious smuggler who has already been sentenced to 79 years in prison. Italy recently introduced an amendment that would designate human smuggling that results in the death of migrants to be punishable by up to 30 years in prison.

The harraga without smugglers

Among migrants taking the Mediterranean route, there is a growing trend of “self-smuggling.” Instead of paying a human smuggler, these migrants band together to buy their own boat, motor, and diesel. Given the difficulties of crossing the sea, these self-smugglers are often from Tunisian coastal communities, where they have acquired some maritime knowledge.

The emergence of self-smuggling is a likely reaction to human smugglers’ primary goal of making a profit. They are known to overload boats or not purchase enough diesel to get all the way to Italy. Romdhane Ben Amor, who is based in Tunis and a spokesperson for the Tunisian Forum for Social and Economic Rights, has observed that “many young people here don’t trust the human traffickers. Many of the traffickers work with the police. They’ll take the migrants’ money, gather them together, and then turn them over to the police.”

In addition to eliminating the riskiness of being involved with human smuggling networks, self-smugglers have the option to land in less-conspicuous places. While large migrant boats dock at Lampedusa, self-smugglers may pick Sicily. Although self-smuggling is more expensive and logistically complicated than going with a human smuggler, these migrants have decided that it is worth it.

But regardless of how asylum seekers choose to travel to Europe, the prevalence of smuggling networks will not diminish until migrants’ underlying motivations are addressed. Coordinated action among the countries implicated in all stages of this wave of migration could begin to lessen the influence of this illicit business.

Cover photo by Olivier Jobard for the European Commission Audiovisual Service and licensed under 2011/833/EU.