It is hard to pinpoint the number of stops that electronic devices make before reaching their final consumer. For most phones, the average can be traced through more than 70 international borders before being delivered to your nearest Apple Store. The most vital component of these devices is often the most underestimated: the chip. These chips, or semiconductors, are embedded into virtually every device used today and represent the future for new technologies – including the artificial intelligence push that is taking the market by storm. These small devices, some only 7 nanometers in length, form the backbone of most technology available today, including LED lightbulbs, solar panels, refrigerators, and ultrasound modules, enabling their incredible processing power and efficiency.

With its broad usages, these semiconductors have grown to become a crucial point of leverage in international trade and relations. However, recently, governments, including the major global players of China and US, have tried to pull more of the process inside their borders and control the supply chain. While this push towards self-sufficiency has clear political appeal, historical precedent has shown the dangers of this. Drawing upon lessons learned from the Soviet Union’s failures to achieve economic self-sufficiency, it is evident that past attempts to localize complex technologies have raised costs, slowed innovation, and created new bottlenecks rather than eliminating them.

Structure and Dynamics of the Semiconductor Supply Chain

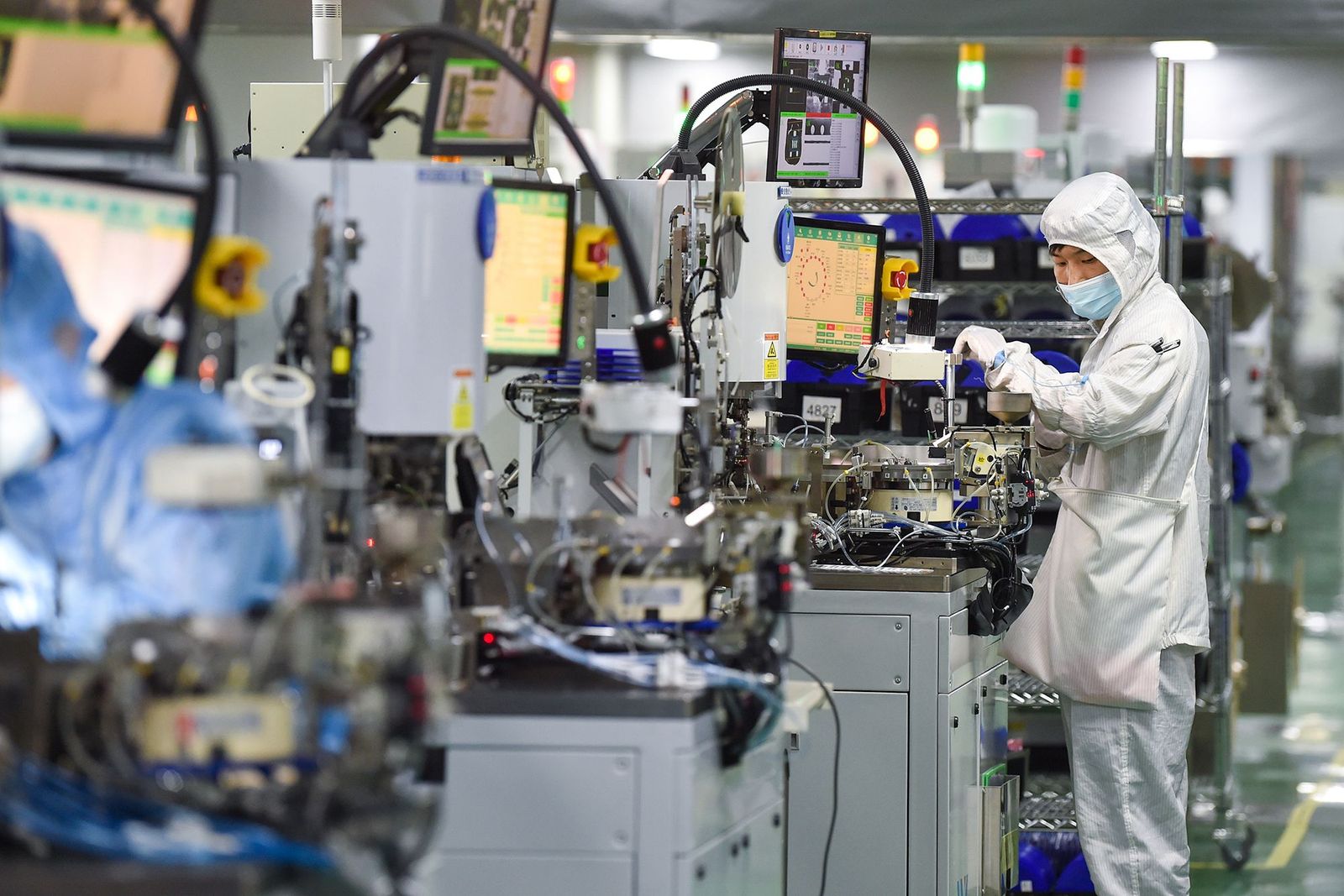

The semiconductor supply chain is transnational and tightly coupled: each stage—design, materials, tools, fabrication, and assembly—relies on contributions from different countries, so small disruptions can reverberate widely.

Semiconductor manufacturing begins in design, where a blueprint of the chip’s architecture is developed with highly specialized software. Thus, core intellectual property, called core IP, has proliferated to lessen the burden of design and assert greater control over the market by private firms that invest thousands of dollars in generating that initial step. The raw and manufactured materials, such as silicon wafers, photomasks, and photoresists, along with minerals such as tungsten and magnesium, that make up the semiconductors, are often in high demand. However, only 5 companies controlled roughly 95 percent of the market in 2020. Fabrication facilities, or fabs, are one of the most critical components of manufacturing, carefully printing the circuits by layering transistor elements whose sizes are measured in atoms onto raw silicon wafers. The precision, scale, speed, purity, and dependability required of semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME) are expensive and difficult to create. As such, the market for this specialization is enormous, with a current valuation of $105 billion and expectations for growth of up to $200 billion by 2030-2033. Wafer fabrication facilities, in particular, are increasingly difficult and expensive. The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) has estimated that a 3 nm fab, the most advanced model, costs more than $20 billion.

Given the complicated steps to produce chips, there has been a clear division of the roles between countries. The United States and South Korea are focused on design and development, Taiwanese giants such as TSMC lead production, Japan and the Netherlands provide manufacturing equipment, and Silicon Valley serves as an overarching hub for talent. With an estimated global market size of $681 billion in 2024 and expectations to grow to $2.06 trillion by 2032, countries are each vying for a larger stake in the sector.

In short, the process to create a single semiconductor is incredibly complex and capital-intensive, with a few choke points that matter outsizedly. With the market growing quickly and governments competing for larger shares, any weak link – whether a materials shortage, an export curb, or a factory outage – can stall output and trigger economic and political tension. Recently, difficulties have emerged as countries increasingly seek to build their semiconductor industry within their borders.

The Dual Move Toward Self-Sufficiency

Although this system of transnational chips has worked over the last decades, questions regarding its future viability have arisen. Competition is becoming increasingly apparent as countries such as the US and China begin consolidating their power to gain an economic stronghold over the industry. Growing individualism has led these major world powers to seek dominance through domestic semiconductor manufacturing. This is especially relevant as semiconductor sales are concentrated in just a few countries. 46 percent of the market goes to the US, 21 percent to South Korea, 9 percent to Japan, 8 percent to Taiwan, 7 percent to China, and only 9 percent to the rest of the world.

In recent months, the Trump administration has been moving toward reducing its foreign dependence. The administration is communicating with Taipei to shift investment and chip production to the US so that half of the chips sold to America are manufactured domestically, although discussions are being complicated by tariff discussions. Specifically, Washington has been working with Taiwanese giants such as TSMC to encourage further investment. TSMC has been building manufacturing facilities in the US since 2020 and has already announced plans to invest an additional $100 billion, bringing total investment to $165 billion. Larger goals seek to reach around 40 percent domestic semiconductor production by the end of President Trump’s term – a move that would require over $500 billion in local investments.

Meanwhile, China has been aggressively pursuing domestic production across the supply chain. On September 15, 2025, the Chinese government banned the use of NVIDIA semiconductors, ordering companies, including TikTok parent company ByteDance and Alibaba, not to buy Nvidia’s country-specific chip. The ban came after Chinese regulators asserted that domestically manufactured chips had attained performance comparable to those of Nvidia’s China-specific chips. Companies such as Huawei, which had previously been struggling due to US export restrictions, have seamlessly stepped in to replace Nvidia. At a Huawei conference, Xu Zhijun, Huawei’s vice chairman and rotating chairman, claimed that current chips are comparable to what was previously on the market and unveiled a three-year release schedule for new chips, which are expected to double their computing power with each new release. While there are still concerns about the validity of China’s technology in comparison to America’s – Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei downplayed expectations in June, saying, “Huawei’s chips are still a generation behind the United States” – initial investments and interest indicate potential for future growth.

Many of these individualistic tendencies are set against the backdrop of mounting economic tensions between China and the US, with tariffs, trade wars, and other economic levers strategically deployed. While not to the same extent, many argue that China and the US are approaching a financial Cold War.

Looking to the Past Through Soviet Autarky

History offers a cautionary parallel: the Soviet drive for economic self-sufficiency. The height of the Cold War took place between the 1960s and 1980s, a time of peak tension between the Soviet Union and the US. While these tensions played out in different contexts, a key similarity is the remnants of Soviet autarky that served as a critical backdrop for the conflict, as well as for the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union. Through the mid-1920s, the autarkic beliefs of the Soviet Union appeared to be a fundamental characteristic of its economy. Plans such as the First and Second Five-Year Plans deliberately pursued domestic heavy industry and machinery production. The USSR aimed to limit imports from capitalist countries and to replicate Western technologies domestically. Although this buffered the country from the worst effects of the Great Depression overtaking the rest of the globe, it left it weakened to future economic growth later in the 20th century. It had achieved extensive military and industrial power, but lagged in consumer goods and innovation due to a lack of resources. Thus, during the Cold War, their economic growth was notably stagnant. In January 1964, the American CIA reported that the Soviet growth rate had dropped from between 6 to 10 percent in the 1950s to less than 2.5 percent in 1962 and 1963. Inefficiencies through the system, a lack of innovation, and resource depletion across the supply chain left the Soviet Union exposed, and its collapse 30 years later could be seen as a foreseeable consequence.

Thus, Soviet autarky, while extreme, presents a warning of the effects of severe nationalism and individualism. Lack of global trade and scientific collaboration has resounding effects across both individual nations, but also for more neutral parties caught between competing powers.

The Strategic Dilemma of Producers in the Middle

With current tensions between East and West powers, smaller countries, including Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, are caught in the crossfire, forced to navigate dual dependencies. As it stands, though, neither the U.S. nor China dominates manufacturing. Instead, Taiwan, through TSMC, produces 90 percent of the world’s most advanced chips and 41 percent of processor chips. However, the U.S. dominates key choke points in the supply chain, and China’s geographical threat grants substantial influence. Thus, Taiwan is forced to adopt a “silicon shield” to protect itself from both parties, hoping that the US would militarily defend Taiwan from possible invasion to protect its critical supply of technologies. It is precisely Taiwan’s current dominance over this critical market that allows it substantial political representation in current discussions, but increasing individualism threatens this “shield” and decreases the small country’s influence.

In addition, South Korea has the second largest share of design revenue globally, controlling 21 percent of the market, and has the second largest share of sales, with over $117M in 2021. Korean companies such as Samsung have significant decision-making power in markets and are tightly interwoven into the supply chain. However, South Korea is facing a similar dilemma to Taiwan. In the past year, China declared its chip technology had surpassed South Korean manufacturing and announced a desire to pull back from South Korean dependence. Meanwhile, the US is proposing annual approvals for exports of chipmaking supplies to Samsung Electronics, alongside SK Hynix’s China-based factories. The country is thus caught in the middle of both parties, facing jeopardy in both of its alliances and leaving strategic vulnerabilities in one of its largest industries.

Implications for Future Semiconductor Corporation

The semiconductor industry will continue to grow at unforeseen rates – far surpassing previous technologies and presenting new challenges for countries to tackle. In our global economy, it is difficult to imagine retracting manufacturing into individual countries. However, current policies across the East and West appear to be making efforts toward centralizing their production of this valuable technology. This can have dire consequences for the smaller East Asian countries left in the middle. Companies based in South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan are struggling to compete with the scale of strong government support in China and are vulnerable to even small shifts in the market. The coming decade will test whether global supply chains can adapt without collapsing into protectionism or following in the footsteps of historical Soviet warnings. Sustained innovation will ultimately depend not on who dominates the market, but on how effectively nations balance security with interdependence — a balance that may ultimately define the next chapter of economic globalization itself.