Furiously criticizing the President of the Czech Senate for visiting Taiwan. Fiercely castigating the organizers of a prestigious international trade forum for not banning European executives that denounced the Chinese government. Frantically condemning the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for a diplomatic visit that an Estonian member of the European Parliament made. The list goes on. Almost every month, European commentators cite another instance that supposedly demonstrates how little Chinese officials seem to understand the liberal, democratic values of the European Union and its member states. As several of them have concluded, “Moments like these have shown that China doesn’t understand the EU at all.” Simultaneously, negative views of China have now reached the highest point since the beginning of the century in numerous European countries. According to a regular poll conducted by the Pew Research Center, the percentage of German respondents having an unfavorable view of China has increased from 33 percent in 2006 to 71 percent in 2020.

Yet, any notions of possible political dissonance between China and the European Union were clearly proven wrong when both sides triumphantly announced the conclusion of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) at the end of 2020. The deal, which had been negotiated for seven years, marks the latest success in a whole series of diplomatic convergences between these two unusual partners. Why have China and the European Union been increasing their cooperation despite seemingly fundamental misunderstandings, to say nothing of their opposing political structures or their similarly contradictory attitudes toward human rights and intellectual property? While it might be impossible to determine a definite answer to such a multi-faceted question, this article will explore the EU-China relationship from an economically based, value-based, and power-based perspective. In comparing the explanatory potential of all three approaches, it will analyze how particularly the power-based perspective can reveal an often overlooked reason for why the European Union and China might have concluded the CAI. This analysis will therefore demonstrate why much of the international criticism that the CAI has received so far is unlikely going to persuade leading European policymakers.

Economics or Values or Both?

At its core, the CAI is supposed to broaden the market access for European investors to Chinese sectors such as electric vehicles and chemical or health services. This objective is set to be achieved through improved legal protections for EU companies, increased transparency of Chinese markets, and lower requirements for entering joint ventures. In turn, Chinese firms are granted enhanced access to strategically important European markets. Apart from these economically-centered clauses, China also committed itself to further reducing the causes of the current climate crisis as well as to ratifying the relevant international conventions on the issue of forced labor. Altogether, economically based and value-based motives seem to predominate the recent agreement on investment.

The economic-based motives are particularly evident. From the perspective of the European Commission, the agreement has been hailed as a considerable “business win” since it is supposed to establish a more equal playing field for European investments in China. As the cherry on the cake, the previously exorbitant amount of Chinese investments in the European Union will now also be limited, prompting policymakers to hope for a new era of increased European competitiveness in the global economy. From the perspective of the Chinese government, the CAI serves its purpose in securing Europe both as a partner in the ever-increasing globalization and as a source of high-level technology. On the one hand, China will be able to further exploit existing economic and systemic divergences to grow more prosperous and more powerful. On the other hand, it will be able to produce technological goods of an increasingly high quality, thereby effectively remaining the “world’s factory.”

Value-based motives were probably particularly present in the minds of EU officials when negotiating with the Chinese side about the concrete composition of the CAI. Although widely contested, some idealist Europeans might still hope that increased integration of China into the international system will provoke the country’s democratization. By discussing economic issues separately from human rights related issues, these optimists foresee wider Sino-European consensus in the economic area eventually entailing wider consensus in the human rights area, as well. When China conceded, during the diplomatic CAI negotiations, that it might permit EU diplomats to travel to Tibet or Xinjiang, regions where the Chinese regime has demonstrably been committing human rights violations, European leaders celebrated this prospect as a superb achievement.

Power and Prestige

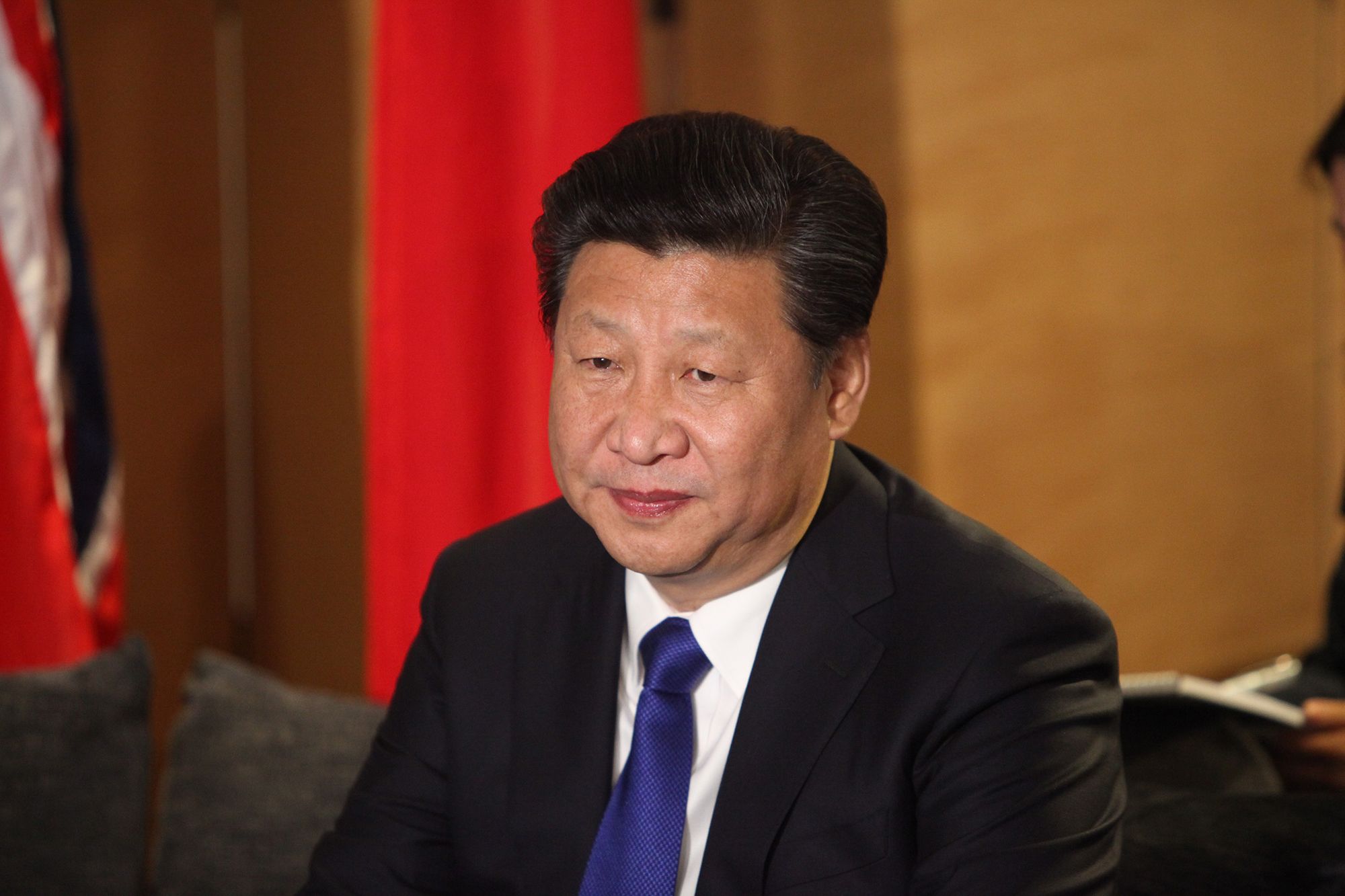

However, many of the clauses contained in the CAI, which were previously introduced as evidence for economically based and value-based motives, can also be interpreted as clauses aimed at increasing the international prestige of both China and the European Union. As many scholars have previously argued, China is highly displeased by the unipolar political order that the United States has established throughout the past decades. While it is hotly contested whether Beijing intends to supersede the United States as the global hegemon or merely intends to assert its dominance in the Indo-Pacific region, achieving either of these two goals would necessitate that China somehow finds a way to limit the international influence of the United States. One such way could be through an expanded Chinese cooperation with the European Union as to promote an increasingly multipolar order. In this sense, the CAI can be regarded as a strategic win for China because it politically isolates the United States and thereby challenges its global leadership. Such an interpretation would explain why Chinese diplomats were eager to pass the agreement at the end of 2020–only a few weeks prior to the inauguration of the new US President Joseph Biden and to the likely renewal of a strengthened transatlantic partnership. It would also explain why Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, has consistently emphasized the CAI’s political implications rather than its economic advantages.

While this power-based motive behind the CAI might have been comparably obvious for the Chinese side, the question remains how the agreement could have possibly increased the European Union’s international prestige. Did European leaders, similarly to the Chinese, intend to establish a more multipolar order without US dominance? Given how many European countries frequently praise and significantly profit from the global hegemony of the United States, such motives seem unlikely. Instead, it is actually the normative power that the European Union has developed throughout the past decades that has been strengthened through the increased cooperation with China. As an article by two scholars from Sweden and Hong Kong argues, EU-China strategic partnerships (like the CAI) should be understood as “arenas in which actors engage in role-playing to assert their international identities and enhance their status.” In other words, the CAI negotiations have allowed the European Union to define certain role expectations that China had to fulfill in order to reach an agreement and vice versa. Both actors could thereby partially project their own worldviews onto the other.

According to this interpretation, what was previously classified as Europe’s value-based motives behind the CAI are actually Europe’s attempts to project their liberal worldview onto Beijing’s Communist regime. Efforts to promote China’s democratization can thus be seen as efforts to prove the moral superiority of Europe’s political ideology. For instance, when China permitted EU diplomats to travel to Tibet and Xinjiang, European leaders successfully exported some of their liberal, democratic values to Beijing. Examples of such value exportation extend past the human rights sector. The Chinese government has also voiced interest in Europe’s expertise with regard to social security as well as health and safety regulations for the workplace. While none of these aspects will themselves transform China into a fully democratic regime, they do massively strengthen the European Union’s normative power on an international scale.

Unheard Criticism

This rise in Europe’s normative power is the fundamental reason why much of the economically or value-based criticism the CAI has been receiving is unlikely to affect European policymakers in any way. Some analysts have suggested the agreement would not sufficiently benefit major parts of the European economy, instead only pleasing “a handful of German multinational companies.” Many others have condemned Europe’s reluctance to coordinate with the new US administration before finalizing the investment deal with China, thereby effectively undermining any possible “democratic consensus” on the issue of how to confront Beijing in the post-Trump era. However, such denunciations have predominantly fallen on deaf ears since they fail to account for the normative prestige that the EU leadership has gained through the CAI negotiations. Although Europe has arguably made a pact with the devil in the sense of cooperating with an authoritarian regime, even the slightest Chinese concession can now be characterized as the successful exportation of the European Union’s supreme democratic values. While Europe might not be leading the world militarily or economically, it at least wants to do so normatively.

Contrary to the conventional wisdom of Europe and China always fundamentally misunderstanding each other, it therefore seems as if both sides were driven by several rather reasonable incentives when concluding the CAI. Besides the obvious economically focused and value-focused motives, particularly the often overlooked power-focused motive serves well in explaining why most CAI critics have so far not had much of an impact. If commentators want to become more compelling in their critique–particularly in light of how the European Parliament still needs to approve the CAI–they should consider how European officials might use this deal as a way to increase Europe’s international normative prestige. Because after all, this agreement much more represents a powerful pact than a cultural clash.

Cover photo by Friends of Europe, CC BY 2.0, accessed via Flickr.