For decades, Latin America has remained a hub for the illicit drug market and a target of international efforts to eradicate the production of cocaine and marijuana. Many scholars attribute the surge of drug trafficking in Latin America to the instability of the region and its complex political and social landscape. However, many places around the world have experienced some degree of similar fragmentation, yet they do not struggle with the emergence of powerful groups that have been able to infiltrate the government and the military while becoming epicenters of drug production.

Even though there have been several attempts to kill it, the illicit drug market has strengthened, and drug production continues to increase. For example, coca leaf production has reached countries like Guatemala and Honduras, whereas previously, only Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador produced it. Understanding how this black market has remained a constant in Latin America in an ever-changing world might be the key to understanding how to dismantle it.

Knowledge and Soil: The Origins of the Illicit Drug Market

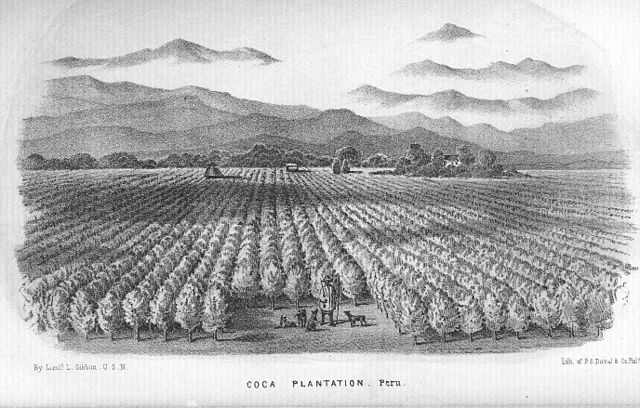

Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug in the world with cocaine following closely behind. Even though both are currently produced in the region, cocaine is endemic to South America. Different from marijuana, whose production spread to most continents centuries ago from Asia, coca (the plant source processed to produce cocaine) has been cultivated by Andean indigenous communities for over 5,000 years, protecting it from being eradicated in their ancestral lands. These leaves are important to the indigenous communities due to their medical properties and ritual usage.

In the 19th century, when European and US pharmacists started to look for new medicines, they traveled to the forests in South America where they found that indigenous communities had been using coca leaf to cure pain and boost energy. Nicolás Fajardo, researcher at the Universität Potsdam, has studied how crossing borders between Europe and the Americas transformed an almost natural product into one of the most popular drugs in the world. He explains that, initially, European scientists started to extract the cocaine from the leaf for medical purposes. However, “cocaine stopped being medicine in the 1940s to become a recreational drug like alcohol or tobacco, with much more fatal consequences.”

Even though scientists knew how to extract the alkaloid cocaine from the leaf, the indigenous communities in the Andean countries were the main group cultivating the plant. As the 20th century advanced, farmers around the region learned to cultivate the coca leaf and sell it to illegal groups that would later synthesize the extract and produce the famous white powder. Since then, the production of cocaine has kept increasing. For example, Peru produces 10 times more cocaine than what the indigenous communities need for medicine and rituals; the rest is directed to the illegal market to be processed into cocaine. Colombia has reached its highest number of coca plantations with 230,000 hectares at the end of 2022. Despite the governments' eradication efforts, the price drug traffickers pay for the prime product and the lesser demand for fertilizers make it a more attractive, highly profitable crop to farmers.

Also, the geographical advantages of the Andes and the Amazonian regions have offered nurturing soil and a sanctuary for these illegal crops and the laboratories where the cocaine is extracted and the drug produced.

When Did Drug Trafficking Boom in Latin America?

When cocaine was first introduced in the international market, it was received with great praise by the highest personalities of the time. Sigmund Freud and John Pemberton, creator of the Coca-Cola recipe, helped cocaine become a widely recognized drug reportedly offering quick energy and improved concentration. It was not until the 1920s that cocaine began to be seen as dangerous and was banned by the US government. Even though cocaine has been a product on the black market since its prohibition, the distribution of the drug did not peak again until the 1970s when young Colombians from humble neighborhoods started to transport it across the Caribbean, exploiting Colombia’s fertile soil and proximity to the United States.

Initially, the fight to control the US market was especially bloody. It was nicknamed the “Miami drug wars” because 50 percent of the homicides in the city were drug-related; these homicides collapsed the morgue system during the late 1970s. The kidnapping of Jorge Luis Ochoa’s sister in 1981 marked a turning point in how the most prominent Colombian narcos interacted. In a meeting, Ochoa and other drug traffickers decided to create the paramilitary group MAS (Death to Kidnappers) to protect themselves and create a united front. Thanks to the alliance, the war among drug traffickers decreased to a certain extent, and the fight in Miami diminish. However, the formation of MAS also helped to skyrocket cocaine production. From that meeting, the first drug cartel—Medellín’s Cartel—was also born, paving the way for the complex drug trafficking structures that we see today. The consolidation of the “business” helped traffickers gain more terrain because they were not worried about fighting with each other but rather other groups that controlled important drug transportation routes.

The cartels were able to put more pressure on the Colombian government to meet their demands through coordinated violent attacks like bombings and assassinations. Pablo Escobar’s death in 1993 and the crackdown on the cartels by the Colombian and US governments in the late 1990s and early 2000s erased the powerful monopoly Colombian cartels had held over the trade for the previous three decades. It opened up the drug market to new players. During the early 2000s, most of the distribution networks moved north and shifted from the Caribbean to the US-Mexican border, which accelerated the formation of the cartels that now traffic in Mexico. At least 170,000 people died between 2006 and 2016 due to the war between the Mexican government and the cartels. While drug traffickers in Colombia were mostly a force against the government, recently, drug traffickers in Mexico have infiltrated most of the hierarchies inside the police and the federal government, gaining more power with less opposition.

Politics and Poverty: The Stabilizers of the Drug Trafficking World

Latin America has long been a deeply unequal region; in 1985, 45.6 percent of Colombians and about 25 percent of Mexicans lived under the poverty line. The income gaps turned people towards the profitable market of illegal drugs to earn “easy money” and escape a life of needs. For example, “El Chapo,” former leader of the Sinaloa Cartel in Mexico, said in an interview that he went into drug trafficking because there were no job opportunities in his region. According to the Spanish newspaper El País, drug traffickers are the fifth-largest employer in Mexico with around 165,000 people involved.

These high poverty levels reflect the instability of Latin American states with recurrent civil wars and military coups. The rural zones where most of the cocaine is produced feel abandoned by the central government due to isolating geography and the political elites’ concentration in urban areas. The lack of law enforcement in these rural areas gives more maneuverability to illegal groups. In the last couple of years, Central America has become a key place in the drug distribution chain due to its high levels of corruption and impunity. The instability of these failing Latin American states creates the perfect environment for drug trafficking groups to thrive.

After 50 Years of Drug Trafficking, Why is the Fight Against Violence Still Far From Finished?

There have been several efforts to eradicate drug trafficking in Latin America mostly sponsored by the US government. The Plan Colombia is one of the offensive plans that the US government has repeatedly called a success. Through the Colombian military, the United States spent US$10 billion in training, armament, and coca eradication strategies to stabilize the country and take away the power of narcotics traffickers. Even though Plan Colombia decreased the power of illegal groups and brought stability during the 2000s and 2010s, the plantations are again quickly spreading, and the elimination of the drug industry by domestic and international efforts seems far away. In Peru, since 1991, the government has also received support from the US government to fight drug trafficking based on the coca plantations and the established routes to Colombia to distribute the cocaine.

Nonetheless, the efforts made by the Latin American militaries have yielded few long-term results. Drug trafficking works as a parallel economy to the legal exportations of the countries, which entrenches it in local economies and therefore makes it harder to eliminate. Even though political instability and poverty are not unique to Latin America, the combination of these factors—along with the fertile soil and the indigenous knowledge to cultivate the coca leaf—created the perfect setup for a thriving drug trafficking market that does not seem close to dying.