In the existentialist play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, the Player, a traveling actor, exclaims that “We’re actors! We’re the opposite of people!” Reflecting a popular sentiment that theater is inaccessible, unrelatable, and removed from the needs of ordinary people, the exclamation overlooks the strides that popular theater (e.g. Hamilton) has made in communicating relatable social messages and bringing new meaning to its audiences, entertaining them all the while.

While the entertainment value may attract most audiences to modern theatrical performances (as they surely did during Shakespeare’s day), playwrights and theatrical troupes across the world have tailored their performances to achieve another goal: conflict resolution. Traditional popular theater and innovative forms of participatory theater, in which actors engage directly with the audience, have started to address a wide range of conflicts at a localized level, ranging from recent and acute violent conflicts to remnantal hostility from past strife. In turn, these methods provide insightful lessons for conflict resolution across the world.

Theater Be My Friend

Nigeria offers an example of successful conflict resolution efforts, both through traditional and participatory theater. Although the struggle against Boko Haram has captured the world’s attention, the international community has generally overlooked a raft of other conflicts within the country. Farmers and herders have fought over land use (with a religious undercurrent), ethnic groups have fought over local governance, and local groups in the Niger Delta have fought multinational companies’ attempts to exploit the region’s oil resources.

However, groups across the country have increasingly adopted theater as a means to resolve these various conflicts. One playwright, Ben Tomoloju, tackled many themes related to conflict in his play Askari: A Vote for Tolerance. In the play, a tyrannical ruler, Lord Askari, embarks on a senseless war against two neighboring ethnic groups. Eventually, religious groups and international peacekeepers combine forces to stop the fighting. Although fiction, the play attempts to illustrate the causes of conflict (identifying competition for resources, a lust for power, clashing value systems, and information asymmetry), the impact of conflict on local communities, and the interests of various stakeholders in conflict. Tomoloju aimed for a realistic depiction of the causes and consequences of conflict, something unattainable in a more formal educational program. In turn, this makes it easier to offer solutions to conflict, as the play clearly elucidates how various stakeholders impact the conflict’s progression, and, by extension, how the various stakeholders can change their actions to resolve the conflict. Additionally, Tomoloju wrote dialogue in several native languages, such as Yoruba, to make it more accessible to local populations. Indeed, the form of theater, with its oral communication, allows it to effectively reach illiterate groups within society. In a country without much of a theater infrastructure, the play reached audiences nationwide, and producers even turned the play into a movie, reaching an even larger audience.

One strand of participatory theater, known as theater for development, has emerged to help resolve Nigerian conflicts. As the anti-poverty group Participate defines it, theater for development “allows communities to write their own stories and perform in a drama based on the messages that emerge from the storytelling process,” often with the help of trained facilitators and involving folklore, song, and dance. In essence, the people become actors. In the Assakio Development Area in central Nigeria, simmering tensions between the Alago and the Eggon people over control of the area’s political structures boiled over into outright conflict after the death of an Eggon man campaigning in Alago territory, resulting in dozens of deaths. In this context, theater for development added a layer of impartiality to the conflict, removing bias and allowing participants to look at their own side’s actions in a different light. Forcing participants to play the other side of the conflict in these impromptu plays allowed them to see the other side of the story. Overall, theater for development allowed participants to view the conflict from a different angle, giving them an opportunity to look critically at the conflict and propose solutions at this new angle.

To Debate or Not to Debate

Of course, theater for development extends beyond the Nigerian context, and other forms of participatory theater have emerged to complement it as well. In Northern Ireland, violent riots in 1969 marked the beginning of a decades-long conflict known as the Troubles, between paramilitary groups representing mostly-Catholic Republicans wanting unification with Ireland and mostly-Protestant Unionists wanting to preserve the status quo of British rule. Even though the 1998 Good Friday Agreement nominally ended the conflict, tensions between Unionists and Republicans still remained. Within a few years of the Good Friday Agreement, several plays were written to help draw down tensions in the aftermath of decades of conflict.

One play took a theater for development approach. The Wedding, about a mixed marriage between a Protestant and Catholic, innovatively took audiences between different physical locations as the play’s story arc developed. Its creator, Jo Egan, brought together community theater groups from both sides of the religious divide, which initially created some tensions when the groups came together to finalize the play. Ultimately, though, discussions about the script built trust between the two sides, and the joint training sessions during the play’s development built at least a tolerance of the other side’s point of view. Many of the project’s participants went on to explore more theatrical options, and the play’s creators felt as if a “critical mass of people who were exploring alternative means of expression other than violence” had emerged. Moreover, the audience witnessed an innovative exploration of identity in the post-Troubles landscape. Critics praised the play, which won both local and national awards for drama, and audiences flocked to sold-out showings.

Another play, though, took a debate theater approach. In debate theater, discussions and workshops linked to a show create space for sharing of stories, opinions, and advice. For example, Yo Mister, acted by ex-prisoners, told three monologues of the Unionist prisoner experience and held discussions afterward. The physical space of the play incorporated the audience itself, perhaps making them more reflective of the experience, and its themes brought up tough topics that ordinary conversations might not usually dwell upon. The use of theater had two diverging effects: although it allowed the audience to visualize the experience of ex-combatants, the fact that performance centered around characters instead of real people created a “safe space” for the post-show discussions, which allowed for frank conversations between the performers and the audience and even between audience members themselves. Alistair Little, the play’s facilitator, believed the interactivity was essential to the play’s messages of reconciliation and forgiveness, allowing the audience to more effectively build understanding and gain emotional intelligence of the other side.

All the World’s a Forum

While debate theater solicits the participation of the audience after the play ends, other forms of participatory theater solicit it during the play itself. In Kenya, Amani People’s Theatre (APT) has offered a wide range of participatory theater projects, tackling issues ranging from post-election violence to bullying. To address bullying in a Nairobi slum, APT adopted a game called Bully, Victim, Savior, in which actors create a skit with three characters in each of the aforementioned roles. Spectators soon take the role of the actors, and the role of each character switches, showing the “malleable power dynamics” of these situations and how various actors can take steps to stop them. In the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya’s northwest, tensions broke out between the local Turkana people and Sudanese refugees, and APT brought in theater for development, tasking mixed groups with producing plays about their experiences. Eventually, the groups created a drama utilizing Dinka song and dance, bringing the two groups together; the performances also brought in refugees from other backgrounds, breaking down cultural barriers and offering a space for dialogue and bonding.

However, APT mostly makes use of a technique called forum theater. In forum theater, actors perform a scene, and then spectators step into the various roles, proposing different solutions and changing the ending of the play as they go along. As with theater for development, the people become actors. Although some of the solutions may not work out, forum theater provides the space to explore these potential solutions and find the ones that work most effectively. APT has used this approach in a wide variety of contexts. Along the Indian Ocean, APT tackled conflicts over land, with the protagonist of their play facing several layers of opposition in a quest to get title to his land; forum theater allowed the audience to propose solutions to this predicament. Forum theater also proved useful after ethnic conflicts in the wake of a contested 2007 election sent shockwaves around the country. It allowed participants to propose new solutions to the conflict, and theater games in general allowed former combatants to visualize a future of coexistence.

Each Man Plays (Back) Many Parts

Rwanda offers another example of the healing power of theater. In the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, tensions between the Tutsi victims of the genocide and Hutu perpetrators reached their apogee, and theater became part of Rwanda’s overall campaign towards reunification and reconciliation. In particular, the Isonga Ballet organized shows with Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa performers, allowing the three ethnic groups to interact with each other. British anthropologist John Ryle commented that the performances, replete with traditional songs and dances, embodied “an idea of ritual social cohesion that has endured through times of wrenching discord.”

Search for Common Ground (SFCG), a non-profit working to transform conflicts into cooperation, introduced both forum theater and another form of theater, playback theater, into Rwanda. In playback theater, audience members tell their stories to the troupe of actors, who then reenact those stories with a bit of improvisation and to the accompaniment of local song and dance. In essence, the actors play real people. By presenting the actions that led to conflict from an outside perspective, playback theater sparks self-reflection, and the new lens allows for new options for avoiding future conflicts. Presentation of conflicting perspectives, meanwhile, creates a level of mutual trust and allows for the exploration of the competing narratives.

“Since participatory theater has been coming [to South Kivu], people are less violent. They’ve been able to find other ways of dealing with a conflict.”

SFCG aimed to address two sources of conflict in Rwanda: land issues and poor governance, and villagers generally proved receptive to the two theatrical techniques involved. They began to recognize the conflicts presented in the plays, their own roles in those conflicts, and the roles of local leaders. Additionally, local mediators took lessons from the plays to look at the roots of interpersonal conflicts, and the plays gave local citizens the tools to reach more peaceful solutions to their conflicts. Justin Malilo, a local official in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the program also operates, buttressed these conclusions, stating that “Since participatory theater has been coming [to South Kivu], people are less violent. They’ve been able to find other ways of dealing with a conflict.”

Koulsy Lamko, a Chadian-born playwright and poet, also experimented with these techniques in Rwanda, staging performances with alternative means of conflict resolution and inviting the audience to contribute to the debate. His performances “allow[ed] the community to heal by transforming collective traumatic experience into art,” while allowing victims to regain the language of collective expression that they lost during the genocide.

Other countries have seen the benefits of playback theater: Following an insurgency in Nepal, playback theater allowed former combatants to hear stories from the opposite side, creating mutual respect and empathy, while playback theater in Afghanistan created opportunities for victims of human rights abuses to tell their stories without the pressures of a formal interview, allowing them to release internalized pain and anger and creating catharsis.

Nothing Can Come of Nothing

Other articles in this issue have explored art’s role in fomenting revolutions and social change across the world, but what happens when the revolution ends and simmering tensions remain on the table? How can countries return to normality in the face of longstanding conflicts and social tensions?

Art, in the form of theater, provides the answer. Some common themes emerged from the various strands of theater. First, the more successful plays worked by bringing opposing forces to the same place and creating a dialogue. Without this dialogue, nobody could change their minds or hear different perspectives on the same conflict. Second, successful plays incorporated local customs and cultural traditions into their performances, giving them additional resonance with local populations that may be scared by imposition of Western cultural norms. Third, the people themselves generated the solutions in the success stories, as local communities are far more receptive to solutions they generated themselves than to solutions they didn’t have a say in creating. In all, theater provides a way of visualizing and humanizing abstract concepts and educating local communities about the ways they can take action to improve their own lives.

In the United States, the election of Donald Trump caused—or reflected—increased polarization between American citizens. Similarly, divides over Brexit in the United Kingdom and disagreements over increasingly authoritarian rule in Eastern Europe have created rifts in many national populations. In this arena, theater (and participatory theater in specific) can give these countries a way to reclaim the common national identities they once had. By bringing people to the stage and letting them give their thoughts a tongue, these countries can begin the process of healing, as so many other countries across the world did. By getting involved in debate theater or forum theater or playback theater, people all over the world can experience catharsis, engage in productive dialogue with the other side, and humanize their counterparts with different backgrounds once again.

Above all, participatory theater blurs the line between actor and spectator, audience members and participants, in order to help people resolve their own conflicts. So the Player was wrong: actors aren’t the opposite of people. They are people, and people are actors.

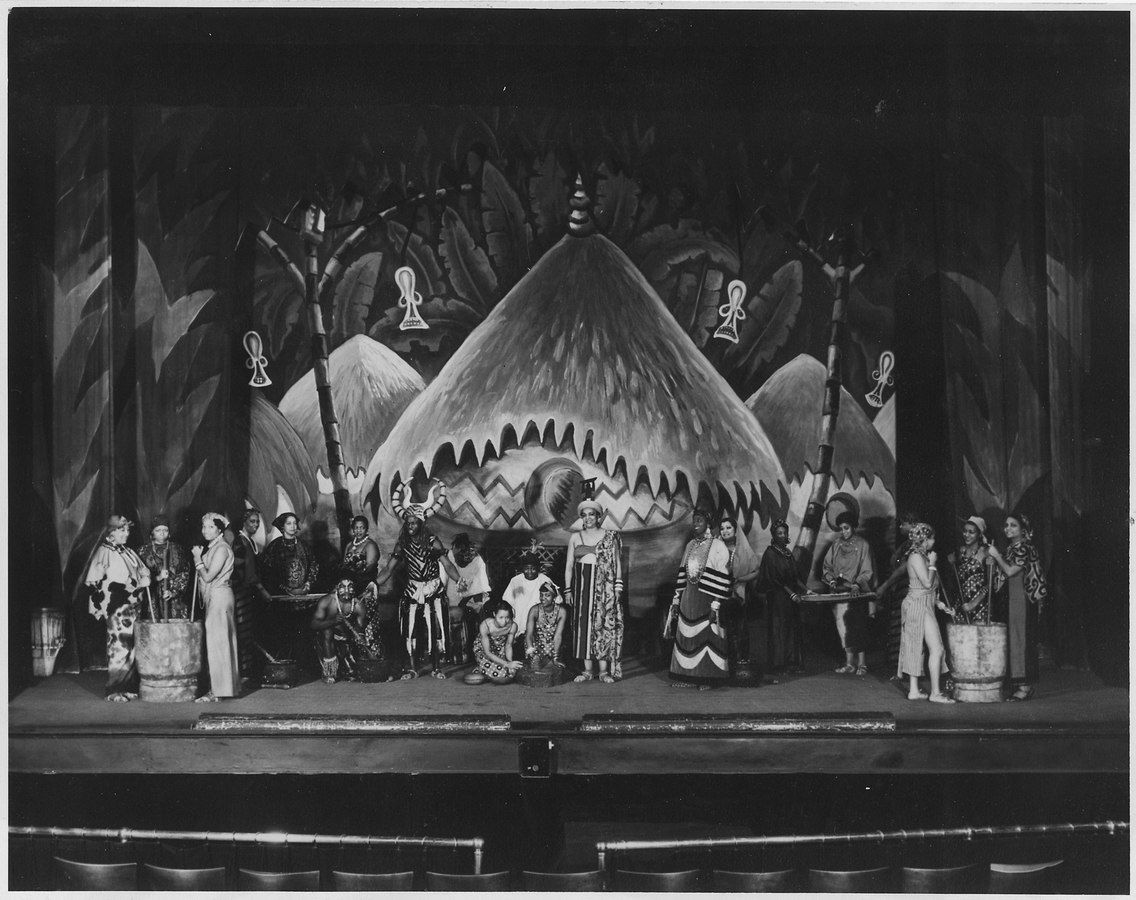

Image credit: "African Theater Group Bassa Moona" by National Archive and Records Administration. Public domain, accessed via Wikimedia Commons.