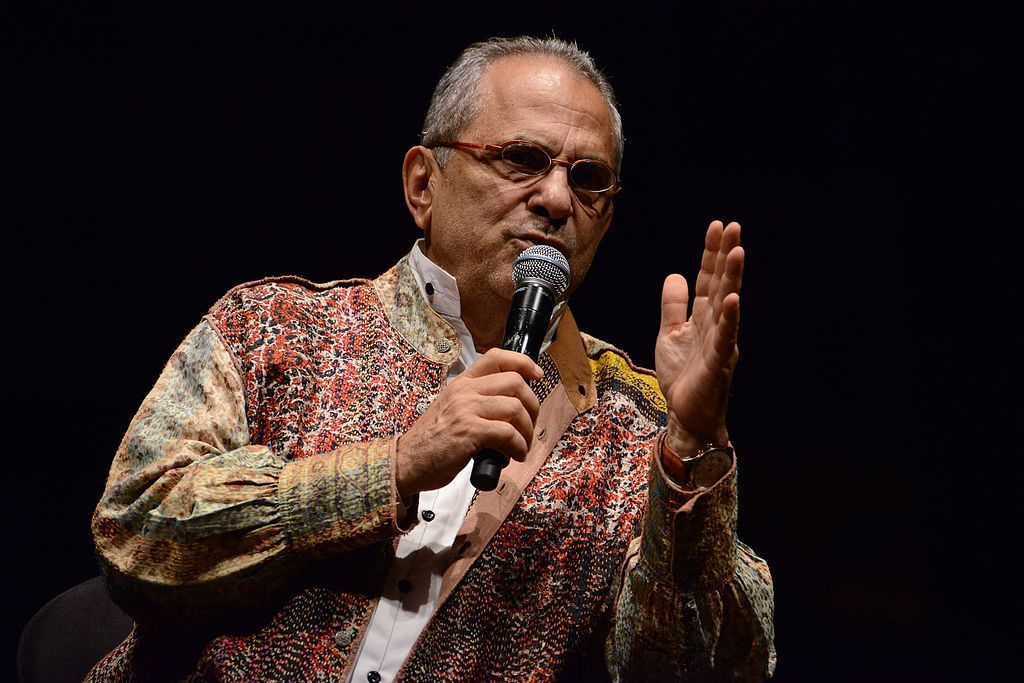

José Ramos-Horta is the current president of Timor-Leste. Between 1975 and 1999, he was the lone voice for the Timorese people as they struggled under brutal occupation. In 1996, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his decades-long “work toward a just and peaceful solution to the conflict in East Timor.” In 1999, Timor-Leste voted for independence; in 2002, it became the first new democracy of the millennium. Ramos-Horta served the democracy he helped to found as foreign minister, prime minister, and from 2007 to 2012, as president. In May 2022, he assumed the office of president for a second five-year term.

The period of Indonesian occupation of Timor-Leste is an often-overlooked example of the ways in which a global binary can have terrible consequences for smaller nations. As you know, Indonesia was able to leverage the Western world’s fear of communism to subjugate the Timorese people, costing hundreds of thousands of lives. How does a country like Timor-Leste, dwarfed by its larger neighbors, navigate the question of alignment today?

It was [a] terrible time for us in Timor-Leste [and] the region. We had just gotten out of the Vietnam War, one of the worst catastrophes, if not the worst, after World War II [and] the Korean War. Up to 500,000 Americans had been poured into [Vietnam] where [Agent Orange] saturation bombing [was] launched not only on Vietnam, but also on Cambodia. Cambodia took more bombs than the combined volume of bombs that fell upon Europe during World War II. So [these were] extraordinarily complex, challenging times because of the defeat of the United States in Vietnam. The dramatic pullout with a US Navy helicopter rescuing people from the rooftop of the embassy in Saigon was very illuminating of US humiliation [by] the defeat in Vietnam. That sent a warning, a fear across Southeast Asia that soon after, it [would] be the countries of Southeast Asia: Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia.

So it was in this context that the Portuguese Carnation Revolution took place and with the implication that Timor-Leste could exercise its right to self-determination, as the new regime in Portugal acknowledged the right of all the people of all its colonies in Africa and Timor-Leste to exercise their rights of the nation. In that context, it was easy for the Indonesian military, genuinely, sincerely, or not, to tell the Western audience [and] leaders [in] Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and the United States that there was a communist threat right in the heart of Southeast Asia. With this pretext, President Gerald Ford [and] Secretary of State Henry Kissinger visited Jakarta on December 6, 1975, [where they] gave the green light for Indonesian intervention, but the US side added, “without the use of American weapons.” Of course, that was a formal diplomatic cliché to protect the US itself. But obviously, the US side knew that any invasion of Timor-Leste would require the use of American weapons, and not the obsolete weapons [supplied] to Indonesia in the 1950s and 1960s from the Soviet Union.

To survive the onslaught that followed, to keep the flame, the hope alive, well, one had to be absolutely inspired, motivated to see tens of thousands of people being slaughtered all over [from] day one of the invasion, to see napalm being used, bombardment from the sea by the Indonesian Navy, helicopters strafing communities. And this went on from 1975 all the way up to 1981, nonstop. In the process, tens of thousands of people had been slaughtered, tens of thousands died of starvation. It was Timorese iron stubbornness that kept us alive and kept us fighting on. And I was the representative in New York. I had been sent to New York in December 1975. That was my mission, to mobilize the so-called international community. The UN Security Council unanimously passed a resolution on December 22, 10 days after the invasion, affirming the right of the people of Timor-Leste to self-determination and demanding that Indonesia withdraw its troops from Timor-Leste, without delay. “Without delay” is a quote from the text of the resolution.

Of course, Indonesia, you know, increased the aggression. And [at] the same time, as Indonesia ignored the Security Council resolution and increased the aggression, the US also increased weapons sales to Indonesia.

But we survived. In the end, [the] Suharto regime didn't survive. They didn't survive age. They didn't survive time. Not only because of the physical age of the dictator, but also [because] the so-called economic miracle of Southeast Asia, the so-called “tiger economies” of the 1980s and 1990s, collapsed like a castle of sand, with a financial crisis that began in 1997 with [the] devaluation of the Thai baht. Followed by Indonesia, the Southeast Asia economic financial crisis also caused a ripple effect in South Korea, whereby hundreds of thousands of people protested and they had elections by December 1997. And President Kim Dae-jung of Korea was elected after more than 30 years of [his] fighting for democracy in South Korea. So, between 1997 and 1999 momentous changes occurred in Indonesia, in Timor-Leste, and in South Korea.

One of your main priorities as president is for Timor-Leste to join ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) at long last. However, the 2021 UN General Assembly vote in which Timor-Leste abstained from condemning the repressive military junta in Myanmar put that into jeopardy. What steps do you think Timor-Leste needs to take to make a compelling case for joining ASEAN?

The requisites for joining ASEAN are two: one, that the aspiring member applying for membership in ASEAN must be in Southeast Asia’s geographic footprint. Timor-Leste is very much geographically part of Southeast Asia; we are not part of any other region. One can be part only of one geographic region by virtue of nature. That's one of the criteria in the ASEAN amended chapter of 2015.

The other one is that we do not belong to any other regional organization, which makes absolute sense. If we are part of Southeast Asia, we cannot be a member of [a] South Asian regional organization. These are the two main criteria. Based on these two main criteria, we should have joined the moment we applied in 2011. Indonesia was very forcefully supporting Timor-Leste to join, together with Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, the Philippines, Brunei. Many countries immediately lined up behind Timor-Leste, supporting our rightful application to be a member of ASEAN.

However, there [were] some reservations among ASEAN countries, not [ones] questioning Timor-Leste’s legitimacy as a member of Southeast Asia, but whether Timor-Leste was prepared to live up to the challenges of membership, whether we had enough human resources to live up to the responsibility [and] agenda of being [an] ASEAN member. So in 2011, an ASEAN task force was created precisely to look at Timor-Leste’s membership, to incrementally support our preparation in terms of human resources, in terms of our economy, peace and security. And we have had tremendous support from the ASEAN Secretariat in Jakarta, tremendous support from Singapore.

In the last twenty years since independence, 700 Timorese have gone to Singapore for training as civil servants, upgrading their skills [and] knowledge, [and getting] full-fledged degrees from different Singaporean universities. But we also have had hundreds of Timorese study in Indonesia, in Thailand, in the Philippines, and Timor-Leste’s own scholarship schemes. We have devoted US$30 million a year since 2009 under a program called the Human [Capital] Development Fund, whereby every year dozens and dozens of young Timorese would go to universities in Southeast Asia, [and] also in Australia and Portugal.

As a result of this tremendous effort on our part, today, if you walk into our Ministry of Finance or our central bank, or any ministry, you will not find many international advisors. 10, 20 years ago, there were hundreds of international advisors under different schemes. Today, in the Ministry of Finance, you [will not] find a single one in our central bank; in some ministries, maybe one or two, here and there. So it means we have come a long, long way in developing qualified human resources with bachelor's degrees, master's degrees, and PhDs from universities around the world, including from the US. The US [has smaller] numbers, but we have had people [who have] been to many universities in the United States. So in terms of human resources, we are not as strong as Indonesia or Singapore, but we have made dramatic progress since the application to join ASEAN in 2011. So we are more than ready.

Of course, you were a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1996 for your advocacy for the Timorese people in the struggle for self-determination. Do you think that contributed to the resolution of the decades-long conflict in any way, and is it possible for similar nongovernmental groups to bring about peace today?

Well, I would say yes and no. Yes, the Nobel Peace Prize contributed to a resolution of the conflict by raising awareness internationally about the problem of Timor-Leste. And I would say not necessarily, because regardless of any external event, of any international recognition of international indifference, our people [would] fight on and would die for freedom. But a positive outcome of the Nobel Peace Prize [was] far greater visibility for myself as the spokesperson of the people, greater awareness about Timor-Leste, including in Indonesia, because the determining factor was always Indonesia. If the Suharto regime had not collapsed under the weight of the 1997 financial crisis, I don't know whether even the Nobel Peace Prize and international pressure would [have succeeded] in pressuring Indonesia to vacate Timor-Leste, to agree to a referendum. So that's why I say yes and no.

The financial economic crisis in Indonesia was maybe the greatest factor in the resolution of the conflict. The post-Suharto President B. J. Habibie [agreed] to a referendum on self-determination. He did so first, of course, as a result of the financial crisis, but also as a result of Indonesia's isolation internationally over this issue. And international pressure, international recognition of any situation is absolutely important. There is no country, no regime that is entirely insensitive, indifferent, [or] immune to what happens around it, around the world. We are all interconnected. We are vulnerable. And if we want to play a dignified, active role in the region [and the] international community, there are rules that we have to observe. And when we violate these rules, we lose legitimacy.

One question that you asked and I didn't mean to ignore was about Myanmar. Yes, for me, it was a disgrace that at that time, our government decided to abstain. Absolutely nonsense by our government, and I have been a firm advocate of democracy in Myanmar for more than 20 years. I have been to Myanmar many times. Way back in July 1994, I was in Myanmar conducting the first ever human rights training inside Myanmar, obviously not in Yangon, [but] in the jungles of Manerplaw, on the border [with] Thailand. It was with a program on human rights that I personally designed [and] introduced in the University of New South Wales in Sydney. I [was] invited by Burmese dignitaries; we conducted a training session of two weeks in Manerplaw. So I know Myanmar like few people. And for me, it was an absolute sadness, to say the least, that my country at the time decided to abstain on the coup orchestrated by the Tatmadaw (the Burmese armed forces). And [at] the same time, I was absolutely pleased that Indonesia took the lead in advocating for [the] return of democracy in Myanmar, which shows extraordinary changes in Southeast Asia. No longer [is] the issue of human rights [a] domestic issue. 20 years ago, there [was] the question of non-interference in internal affairs, [including] on issues of human rights violations.

Of course, that cannot be sustainable. When human beings have been killed, or been tortured, it doesn't matter where—we are all responsible. No one, [anywhere] in the world, should have the right to imprison, to torture, to kill with absolute impunity. It doesn't necessarily mean that every time such situations happen, you have to speak through a loudspeaker. There are many different ways of trying to help. I personally advised the UN Secretary-General and some countries [that] sometimes it is better to take, at least as a first step to address a situation, the low-key approach. And I always say, if I can save one single life from torture [or] from execution by staying silent, by approaching the case through quiet diplomacy, I prefer the latter, rather than speaking out. If I can talk to the regime, to the leaders in the country, to please save the life of such prisoners. I'm not speaking out in public, I'm not putting out a statement, I just beg you to save, to spare the life of the person. I will be prepared to do that rather than making grand statements.

So I understand. I was a street activist fighting for human rights. I [have been] in the trench of civil society, I have been in the government, out of government, begging the government, and I know how one has to be pragmatic, creative. If we are motivated by stopping torture, stopping killing, then we have to be intelligent, pragmatic to see what is the best approach to [saving] the lives of our people, to [saving] the life of someone who is in prison. Whether it's through a grand statement, a UN resolution, the Secretary-General, or the High Commissioner for Human Rights, that's how I approach [it]. But in the case of Myanmar, when there is a coup, with [the] slaughter of people, there is no longer space for quiet diplomacy. The world has to speak out. And the world has spoken out on Myanmar, but with absolutely no result. So we have to look at how to expand sanctions on Myanmar’s military, how to call on China to live up to its responsibilities as a major power, as a permanent member [of the] UN Security Council, and as an aspiring member of [the] Human Rights Council because China is now seeking to be reelected, [to see] what it can do to reverse the situation in Myanmar.

Timor-Leste is such a young country—this year marks the 20th anniversary of independence. Since then, you’ve been elected to the presidency twice, in addition to your time in several other government positions. What lessons does Timor-Leste have to share with the rest of the world about the emergence of a nation?

Well, our experiences or lessons are that we have to stay focused on what we want to achieve. And staying focused also means [being] creative, [using] our mind, our intelligence, and the incredible availability of social media, of connectivity, to bring the international community closer to us. [The] lesson is: do not allow yourselves to be consumed by anger, by hatred. Open up, be humble, but be dignified, be proud also. Humility is a strength and arrogance is a weakness. Pragmatism is a necessity. Dogma is suicidal. You know you cannot govern with dogmas. Only the Bible, the Quran, and all other religious texts [are] unchangeable, but constitutions, laws, and political statements are all made by human beings. We have to adapt them as time goes by. And so my point is, stay focused, but be creative, be active, do not lose hope and do not surrender to anger or hatred. Always try to reach out, build bridges, including with those who say they hate you, those who call you [an] enemy. Eventually they will change, if you pursue your struggle, your advocacy with intelligence and humility. Humility is a virtue of the truly great people. Arrogance is a killer of individuals. They don't survive. Only the greatest people, like Mahatma Gandhi, like Mandela, like [Martin] Luther King [Jr.], and people who always espouse humanity, compassion—their messages survive the times. Their lessons inspire us.

Varada spoke with Ramos-Horta on July 16, 2022. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Cover image: José Ramos-Horta at the Fronteiras do Pensamento conference in Porto Alegre, Brazil, on September 30, 2012. [Photo by Fronteiras do Pensamento]. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.