In 2019, the EU held parliamentary elections, one that would serve not only to seat a new legislature, but also to act as a referendum on the state of Europe. In the years since the last elections in 2014, the European Union had been battered by challenges to its core: a refugee crisis, financial failures, and Brexit. In response, voters across the continent began electing far-right and nationalistic governments domestically. Fidesz in Hungary, The League in Italy, and the Freedom Party of Austria rose to power on platforms against immigrants and European integration. At the same time, the rise of the climate crisis meant a wave of left-leaning green parties, usually called the Green Party, ascending to national governance. After losing voters on both sides, it was no surprise that the election results were dismal for the center in Europe. The far-right had increased their representation in the European Parliament to 25 percent, and the Greens had added 25 seats to their bloc, both largely at the expense of the European center-left.

This unprecedented blow to the traditional political order meant that the long-ruling Grand Coalition of the center-left and the center-right received only 44 percent of seats in the parliament. But on a larger level, the European elections were simply a reflection of the center-left’s fall from grace within the European countries, including the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in Germany, the Socialist Party of France, and Labor in the UK. Without the center-left, governance in Europe has lost its stabilizing force. Since 1945, the center-left has played a vital role in almost every major democracy in Europe by being part of either the government or the opposition. The center-left’s failure to reform and adapt to the present challenges of the EU has sent shockwaves beyond the parties themselves, including feeding into alternative political parties and the loss of cohesive social policy across Europe.

Embracing the Market

In a way, the decline of the center-left was somewhat foreseeable. The market-regulatory policies ushered in by the center-left after World War II created a remarkable period of stability within the European economy. The flood of investment from the Marshall Plan and a boom in industry brought a high increase in the quality of life for almost all West Europeans. But while recognizing the economic growth through increased capitalism, European center-left leaders were skeptical of its stabilizing effects. In previous decades, speculative markets and lack of security had contributed to the Great Depression, financial insecurity, and the rise of nationalistic sentiment. Therefore, strong trade unions, government saving, and sustainable growth became focuses of these governments. Through these policies aiming to prevent economic windfalls, the following quarter century was the period of highest growth in Europe, according to data from the World Bank. The center-left leaders also realized the limits of capitalism in equitable development, and thus redirected vast amounts of funds to stronger welfare states, propping up education and healthcare to redistribute the economic boom to its citizens. In return, European countries were able to deal with social issues with fair stability. In doing so, the center-left presided over a period of stability both economically and socially.

The center-left of the last decade has failed to reflect any of these sentiments by straying away from their post-war roots. Instead of cushioning workers and voters from the destabilizing effects of the market, many European center-left parties instead turned to an embrace of the market. While nonetheless supporting a social security net, leaders like Gerhard Schroeder of the SPD in Germany stopped their critique of capitalism as the source of inequality itself. Instead, at some points, these “Third Way” parties became indistinguishable from the center-right in many of the same countries. Tony Blair’s New Labor in the UK separated itself from the labor unions that had traditionally been its backbone. And amidst the disastrous financial crisis in 2008, the center-left bailed out big banks just like the center right, while imposing austerity measures onto their workers to pay for it.

Since then, in the instances where they have governed, center-left parties have been in leadership at a time when wages are gradually becoming more inequitable, and more of corporate profits are going to shareholders. Data from the OECD notes that income inequality now is even worse than it was one generation ago. In essence, the center-left has failed to curb the very issues they were voted in office to solve.

A Changing Society

A key source of the post-war stability in Europe was also the sense of solidarity that the center-left parties provided, often tied to the idea of a paternalistic state. Strong social security systems gave individuals a sense of certainty, knowing that their governments had their backs in a worst case scenario. In return, voters felt a strong sense of national loyalty towards their states, electing the center-left and center-right and agreeing to their program of higher taxes. Yet, in the last few decades, the social order of Europe itself has changed. The signing of the Schengen Agreement in 1985, leading to free movement between EU countries, has led to greater internal migration. Simultaneously, more immigrants also have been coming from outside the European Union from countries such as Turkey and Morocco.

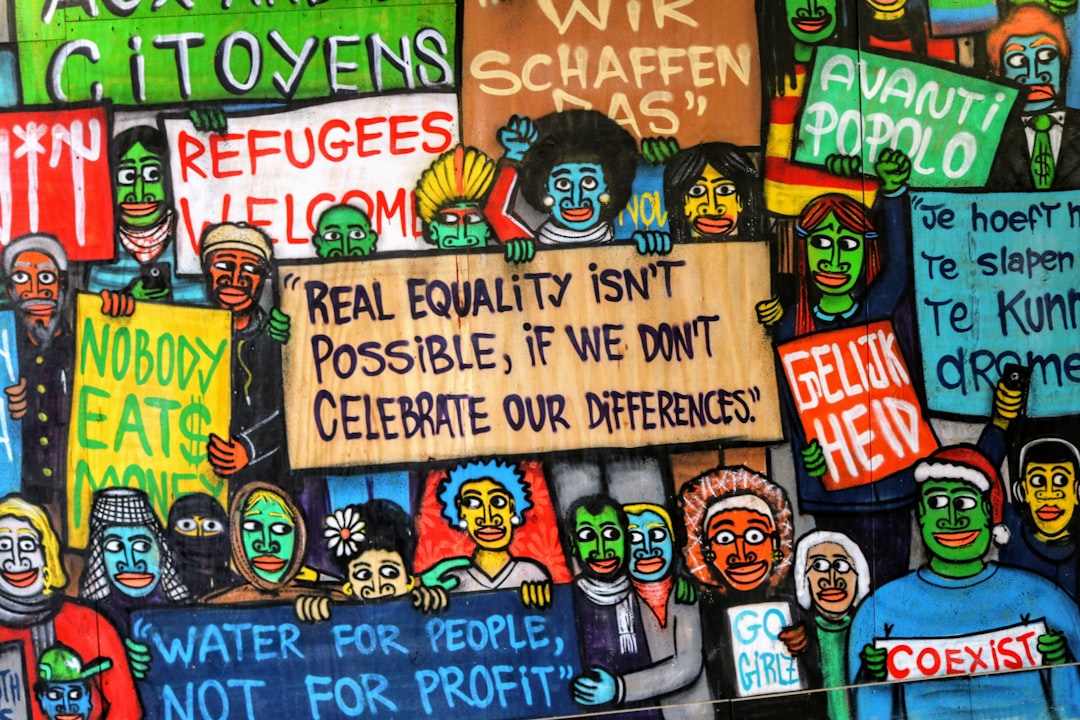

Social and cultural tensions resulting from a changing society chipped at the cohesive fabric in Western European states, which have largely been ethnic nation-states. Especially after the September 11 attacks, public anxiety about Muslim immigrants has made integration more difficult for some immigrants. The center-left’s inability to address these social issues with coherent policy resulted in many wondering what the center-left stood for. There was no direct rebuke to the nationalistic and sometime racist rhetoric of the far right, which views immigration in a much more negative light. Unable to craft a coherent narrative about their vision of society going forward, center-left parties were unable to amass the social and political capital needed to support their traditional program of the welfare state and high taxes.

In their absence, the far-right has been able to gain significant traction. Instead of shying away from discussions about globalization and multiculturalism, parties such as the Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD) have addressed the topics head on and presented them as lethal challenges to a country. Their main support base has come from the traditional voters of the center-left: workers, lower-income families, and individuals of lower education, precisely those who perceive they have the most to lose by social and cultural changes. The right’s rhetoric about strong leadership has a very strong appeal to those who perceive the loss of stability in their lives, whether from immigration or from globalization. In the wake of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to open up Germany to refugees from Syria and other key zones in 2015, the AfD presented themselves as the only “defender” of the German national identity. By providing a clear “alternative path”, the AfD was able to launch an almost-deadly threat to the traditional order in the Bundestag after the elections in 2017, becoming the third largest party with 13 percent of seats. At the same time, the SPD, which had internal party strife over their vision for Europe, gained only 20.5 percent of votes, the lowest since WWII.

Instead of shying away from discussions about globalization and multiculturalism, parties such as the Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD) have addressed the topics head on and presented them as lethal challenges to a country.

The populist movement gained steam on economic issues, but has remained at the forefront of European politics due to its opposition to cultural liberalization and their emphasis on perceived loss of national sovereignty through mass immigration. By using immigration as a key political talking point, the populists across Europe also attack the multinational organizations that have traditionally promoted stability and order. They have been winning so far, with the ANO party in Czechia and the far-right anti-immigration League in Italy as prime examples. These rises in power are usually directly correlated with losses for the center-left, even in liberal bulwark Scandinavia, where the rise of nativist parties are growing.

At the same time, the populist right does not prioritize liberal democracy or human rights. They often attack the free media as being unfair to them and the systems of checks and balances biased against them. Focus on solidarity of race or ethnicity ostracizes and even invites violence and harassment against minorities. These stand in stark opposition to the core European values of equality and rule of law, as written into the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. If the populist right is left unchecked, their hold over Europe can only grow.

A Green Wave

Before the May 2019 elections, 77 percent of a sample of EU voters cited global warming as one of their key issues for the election. This poll was indicative of a trend over the last few years, with the environmental movement coming out of the fringes and making its way toward the mainstream. Individuals like Greta Thunberg mobilized young people, while groups like Extinction Rebellion drew awareness to the issue. The results of the European Election displayed this acute awareness as well. The European Green bloc surged to become the fourth largest group in the European Parliament, making them an essential party whether in opposition or governance. As a show of their legislative sway, the new Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, put forth a “Green Deal” package.

Much of this surge in the Green Party was at the expense of the center-left. The Green parties are strongest in the well-off nations in the North and West of Europe: Germany, Benelux, the Netherlands, and the Scandinavian countries. The majority of the supporters of the Greens are young, university-educated, and middle class. In the past, much of the Green Party’s success was due to its alignment, for better or for worse, with the social democratic left, which was slow to respond to the environmental questions posed by the movement. In Germany, the Greens were often junior coalition partners with the SPD, while in Spain and the United Kingdom, the center-left have vied for votes against the Greens. Now, the Greens have opened themselves up to governing as a minority partner with a conservative parties, as in the case of Hesse and Baden-Württemberg in Germany. In such cases, the Greens and Conservatives govern conservatively, both economically and socially.

Indeed, the middle-class and educated voters of the traditional center-left seem to have flocked toward the Greens, who seem to be addressing their most pressing issue. In 2017, the Green Left Party in the Netherlands won 14 seats in Parliament, greatly boosting their vote over the four seats they had in 2012. Their leader, the charismatic 30-year old Jesse Klaver, advocated a platform of social unity, reduced coal emissions, and a plastics tax. In doing so, the Greens emerged as a large force in opposition to the majority-conservative government formed directly after. So has been the pattern all across Europe, with the Greens gaining steam for their environmental focus. The social democratic left has lessons to learn from them about voters’ key priorities.

What Comes Next

The competition between the center-left and the center-right has been the source of much of Europe’s stability in the post-war period. The two parties balanced each other out, offering diverse solutions to issues while never moving too far from the center. However, now that the center-left is beginning to approach its death in much of Europe, the very organization of democratic politics has become unraveling. In Germany, five parties sit in the Bundestag, leading to the longest coalition talks in history, while in the United Kingdom, Labor could not even make up its mind over their approach to Brexit. With many of the new parties focused on single issues, such as the environment or immigration, larger and overarching issues such as market regulation, social integration, and equal distribution are left untouched. As such, it seems that many of the issues currently plaguing Europe will be unresolved for the foreseeable future, feeding into more nationalist and populist fuel.

Perhaps more dangerously, the lack of a center-left has meant coalitions tread on dangerous ground. In the German state of Thuringia, state elections resulted in a large split in parliament, especially with large parliamentary blocs with the leftist Die Linke party and the nationalist Alternativ Für Deutschland party. In a stunning secret ballot upset, the leader of the Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP), the libertarian party, was elected as minister president of the state despite the FDP barely clinching above the five percent threshold. In addition to the support of his own party, Thomas Kemmerich of the FDP gained votes of the Christian Democratic Union and the AfD. It was the first time in German history either of the center two parties had entered government with the support of the far-right party. Even more upsetting to many members of the German public was evidence of a possible internal deal between the parties.

The center-left has hope for the future, if they can reflect internally and realign themselves. The “Golden Ages” of European center-left parties, as in directly following the World Wars, is no longer attainable. The rise of multinational corporations, the trend of intercontinental migration, and the trend towards individualism have changed the rules of the game. But the values for which the center-left once stood—for bridging the gap between what workers desire and the inherent social structure of capitalism—has as much relevance, if not more, than ever.

To start, the center-left must acknowledge the current challenges faced by working people across Europe and listen to their voices. The goal is not to shun multiculturalism, globalism, or social changes, as in the instance of the far-right, but to confront the issues within society and to regulate their influence. Just as many people protest growing inequality, this means returning to a role of advocating for a stronger social welfare state and decrying the neoliberal influence of the Third Way in recent decades. Without doing so, there is no one in Europe who hears and addresses complaints of inequality, societal alienation, and unemployment. By actually listening to their voters, the center-left can be able to defeat the narrative of the far-right that governments have neglected to care for its citizens.

Moreover, the center-left must realize that the environmental movement is deeply rooted in the future of Europe and listen to the voters’ demands. No talk of development or equality can ignore the issue any longer, especially as voters leave en masse for a party focusing on these issues. The future of social democracy rests in either being able to collaborate closely with the Greens or perhaps even a merger of the two movements. The Green Left, in the Netherlands, for example, is a merger of four progressive parties who agreed on a unified environmental and social justice platform. A “Green New Deal” in the vein of what has been proposed in America can also be a reconciliation of the social and environmental agendas.The time to act for the center-left in Europe is now. The European elections of 2019 should have served as a wake-up call, indicating that Europe believes the current state of the center-left does align with their vision any more. In the face of a rapidly changing world, the center-left cannot wait any longer. If they refuse to adapt, then they will become obsolete—and Europe will take much longer to recover from its current political situation.