A tall, ice-cold glass of Canadian milk is filled with plenty of calcium, vitamins, minerals, and political controversy. In most countries around the globe, the most feared financial powerhouses in lobbying advocate on behalf of the largest sectors representing oil, pharmaceuticals, and tech. But in Canada, the government and political leaders have been engulfed by the power of the calcium-strong grip of Big Milk. The Canadian dairy lobby pours CA$80 million (US$62,268,928) to CA$120 million (US$93,403,392) into maintaining relationships on Parliament Hill; searching the word “dairy” in the federal lobbyists registry database yields nearly 7,000 results, with dozens of firms making the dairy farmer’s presence felt. In Canadian politics, there is no escaping the grasp of what Canada’s premier current affairs magazine, Maclean’s, has dubbed “the dairy cartel.”

The efforts of the Canadian dairy lobby over the decades have had incredibly far-reaching effects. Canada’s dairy industry has been regulated by a government board known as the Canadian Dairy Commission since the invocation of the Farm Products Marketing Agencies Act in 1972. Unlike commodities such as beef and grains—which hold greater economic importance than dairy—Canada’s dairy, chicken, egg, and turkey industries are controlled by a policy known as “supply management.”

An Udder-ly Controversial System

Supply management is an agriculture policy crafted to enable farmers to be appropriately compensated for their commodities while creating a stabilized supply to the Canadian consumer. This system rests on controlling three key economic determinants: production, pricing, and import. In practice, the policy fundamentally boils down to allowing the Canadian Dairy Commission to limit the production of dairy products, preventing milk from being poured down the drain where dairy farmers bear the brunt of the economic impact.

The Canadian Dairy Commission is responsible for setting production amounts, which are based on forecasting consumer needs and then determining specific production amounts for farmers. But not any farmer can produce and sell dairy; they require a quota, which is a license to produce within the country, limiting its membership to a tight-knit inner circle of dairy farmers. There are only 16,000 farmers permitted to produce and sell a predetermined amount of dairy within Canadian borders, far fewer than the 62,000 non-supply management Canadian cattle farmers.

However, the Canadian Dairy Commission does not stop with limiting producers. In order to ensure price protection amidst market dips and instability, the board sets a price for itself to purchase the dairy products they have allowed to be produced. This board then takes on the task of ensuring the dairy gets from farmers to appropriate companies and is ultimately distributed to the consumer.

On its surface, this appears to be a seamless regulatory system. It is well-protected, and even entrenched into Canadian law that reads “Dairy producers must have authorization for every litre of milk they sell to processors.” Yet there is an underlying factor that forms a colossal flaw: it is a system that would be undermined by imports and foreign competitors flooding the Canadian market. As a result, after the formation of the Canadian Dairy Commission, the Government of Canada swiftly became home to some of the world’s most aggressive and costly dairy tariffs. Today, dairy products from foreign producers are subject to a nearly 300 percent levy before they can become available to the Canadian consumer.

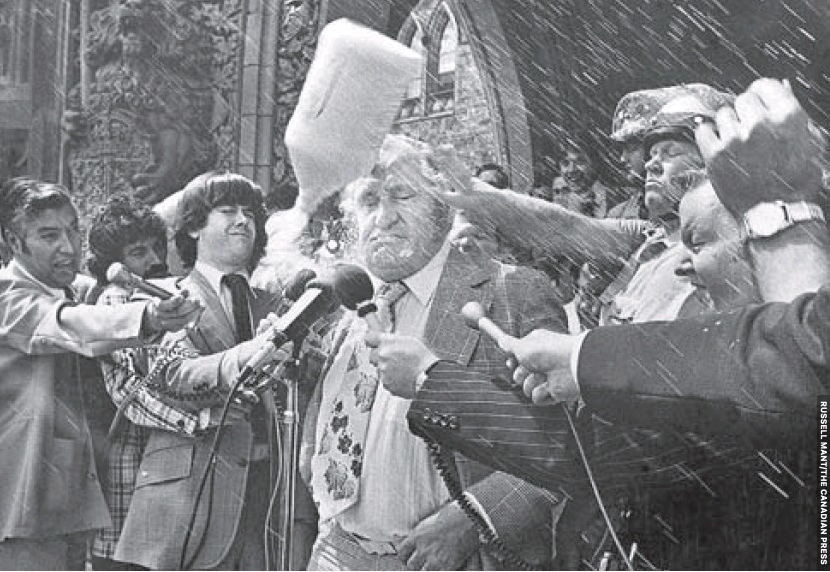

This government protection and formation of a carefully crafted anti-competition system stems from the 1970s, when Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau introduced these new limits for the dairy industry as a result of overproduction. His government aimed to match production levels with market demand to create a stable market with controlled prices. These moves sparked outrage among dairy farmers in vote-rich Quebec, and they headed to Parliament Hill to challenge Eugene Whelan, the minister overseeing the legislation. The Quebec farmers protesting unleashed their frustrations on Whelan, publicly humiliating him; before Whelan could manage to speak on the amendments to the controversial legislation, farmers dumped milk on his head and knocked him with a jug. This sent a clear message to the Canadian federal government that stands to this day: dairy farmers’ demands are no trivial matter.

The Canadian Dairy Commission, formed by the Pierre Trudeau government 50 years ago, has worked in favor of dairy farmers across Canada. Yet there is a major difference between the member composition of the Canadian Dairy Commission’s board of its conception–that sparked outrage–and the one that exists today. Presently, the Canadian Dairy Commission is run by dairy farmers and relies on information provided by dairy farmers to make its decisions. University of Guelph Professor Dr. Simon Somogyi has expressed skepticism by reasoning that the Canadian Dairy Commission, being a government commission, should abide by the practice of government, work in favor of all citizens and hold stakes in their best interests. Somogyi observes that the dairy farmers’ control of the board creates an environment without accountability to the rest of the Canadian people. This becomes concerning when this very commission is tasked with price adjustments that raise profits for farmers and costs for consumers. Despite the evidence of price fixing, the dairy lobby insists it is engaged in an entirely fair and transparent process.

The Only Alternative

Decades have passed, 16 federal elections have been called, and 8 different Prime Ministers have held office since the Canadian Dairy Commission came into existence. Every one of those administrations endorsed supply management, regardless of their partisan stripe. Their reasoning, which still holds merit in this debate today, is that the only other logical alternative is direct financial support to farmers, in the form of subsidies. But even scholars like Bruce Muirhead, of the University of Waterloo, side with politicians in bluntly saying that is not feasible. Muirhead has gathered ample data proving subsidies would be more costly for the Canadian taxpayer. Projections from a Waterloo political think tank valued these subsidies in the range of CA$50 million (US$38,959,000) to CA$55 million (US$42,854,900) annually. Muirhead in conjunction with the think tank concluded in his published research paper “Crying Over Spilt Milk” that these subsidies would seriously disrupt the balance of the federal budget. As a result, supply management has endured criticism from some scholars and has been praised by others for making farming sustainable without taxpayers footing the bill.

Milking the Political System

Supply management, however, is not an equitable solution. The deep pockets of the Canadian dairy lobby have entrenched it into the structure of Canada’s economy and politics. The lobby’s presence in the nation’s capital is strong, perhaps the strongest of any lobby in Canada. As such, it is no surprise that they have found significant ease in cozying up with Ottawa’s most influential and political elite. The lobby has infiltrated the ideology of Canada’s four major political parties, cementing supply management and the Canadian Dairy Commission into all of their election platforms, despite otherwise contrasting views. Off the campaign trail, parties remain stalwart supporters of nearly all the lobby stands for. There rarely is a week that a Member of Parliament does not stand before the legislature to praise supply management.

Even Canada’s furthest left-leaning party, the New Democrat Party, which touts itself as “For People over Profit” had its leader Jagmeet Singh pledge to “protect supply management and stand up against unfair tariffs.” during the most recent election campaign. While at the same time an academic journal resurfaced and made headlines declaring that supply management unnecessarily costs the average Canadian household an extra CA$444 (US$347) annually.

Perhaps there is no person in Canadian politics better positioned to stand firmly in the corner of the dairy lobby than the former leader of the Conservative Party, Andrew Scheer. Scheer was a rising star in Canadian politics; at 40, he led the Conservatives through an election and came closer than any leader to unseating Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government. Yet, Scheer’s rise to stardom was largely the work of the dairy lobby. During the 2017 Conservative Leadership Race, Scheer trailed the anti-supply management candidate Maxime Bernier on the first twelve ballots, until the final ballot. Scheer courted members of the dairy industry in vote-rich Ontario and Quebec to push him over the finish line and defeat Bernier. Scheer was a lifelong dairy advocate with nearly a dozen year record backing farmers, and memorably credited chocolate milk for saving his son’s life. Experts with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation attributed this so-called “streetcred” with farmers for catapulting him to leadership of the Conservative Party.

After this unexpected victory, Scheer continued to cement his status as the lobby’s faithful warrior. A year later at the 2018 Conservative Party Convention in Halifax, where nearly 3,000 party members gathered to debate and vote on policy, there was substantial momentum behind a motion to abolish supply management from the party’s platform. Leaked documents from dairy lobbyists in attendance revealed Scheer was planning to exercise his far-reaching powers as leader to quash any such policy passed democratically. The news caused an uproar within the party. Scheer’s office quickly denied the allegations. Hours later, a spokesperson from the lobby confirmed the authenticity of the documents, and in regards to Scheer’s view on supply management his Chief of Staff said “he isn’t going to change his mind about this.” Four years later, as Scheer has fallen out of the political limelight, he is still set on protecting the dairy lobby. This March, he endorsed Pierre Poilievre–a pro-supply management candidate–to be the Conservative Party’s next leader in a field divided on the issue.

I spent thousands of dollars to get to #cpc18, and it turns out that there was a coordinated effort between Big Dairy and @AndrewScheer to betray members and our right to be heard. The outcome was predetermined, our voices don't matter. #cdnpoli #abpoli pic.twitter.com/zRAXPtFabD

— Keean Bexte (@TheRealKeean) August 26, 2018

Scheer is not the only politician in Canada who is absorbing the dairy lobby’s agenda like a cookie in a glass of milk. On June 1, 2022, World Milk Day, dairy lobbyists delivered free glasses of milk in front of the House of Commons to Members of Parliament, prompting a member of the Bloc Quebecois, the third largest political party, to praise supply management on the floor of the House of Commons.

The pressure from the dairy lobby is all around Canadian politicians. They are a unique lobby because, unlike the perceived scandalous oil and tobacco lobbies, sharing a glass of milk with a dairy lobbyist does not raise the eyebrows of the public. It can be seen as reputable, without corruption, for politicians to advocate for the interests of farmers. Nevertheless, politicians falling into the hands of the dairy lobby is dangerous for the average Canadian. The Canadian Dairy Commission hiked dairy prices twice this year, for the first time in its history, totaling at a whopping 9.9 percent. They cited inflation, but the inflation rate was a mere 7.7 percent when the hike was announced. No Member of Parliament has stood up on behalf of Canadians to question this price gouging or the dairy lobby’s obscene power. It comes down to one question now for Canadian politicians, how many liters of milk are their morals and dignity worth?