“While I may be the first woman in this office, I will not be the last.” These were Kamala Harris’ historic remarks during her victory speech after being elected as the first female US vice president. Her achievement is one example of women rising to leadership roles worldwide in recent years, from CEOs like Jane Fraser of Citigroup and world leaders such as President Ursula von der Leyen of the European Commission. This growing presence of women in positions of power reflects their determination to shape the future and amplify their voices in a world that, just a century ago, was dominated by men.

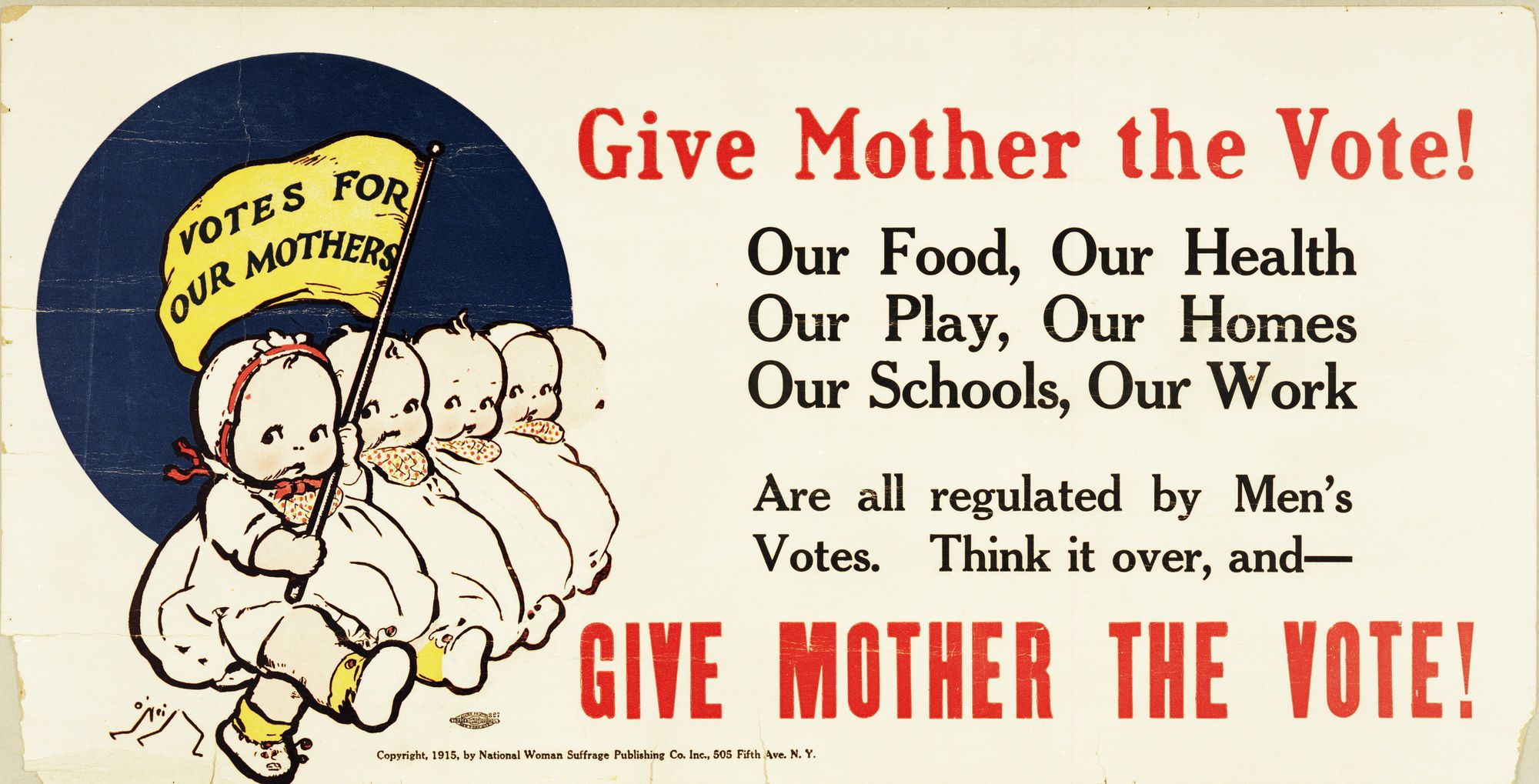

This change was made possible by the pioneering efforts of the female suffrage movements that began in the Asia-Pacific, Europe, and North America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, highlighting women’s demand for a political voice to influence education, economics, and society as a whole. This article delves into the evolution of feminist waves and their transformative impact on Western society while exploring the challenges and opportunities for the modern feminist movements in achieving gender equality globally.

How Did We Get Here?

When one thinks of the female suffrage movements, the most familiar examples often come from the United Kingdom and the United States. However, women’s leagues emerged in all corners of the world. In New Zealand, for instance, female suffragists rallied women from all walks of life to gather petitions, demonstrating widespread public support for a bill granting women the right to vote. The suffrage movement had a broad enough base of working-class, rural, and educated elite populations to strengthen their argument in parliament. In 1893, New Zealand became the first country to pass a bill granting women’s suffrage.

It is important to distinguish between suffragists and suffragettes, even though newspapers often used the terms interchangeably. Suffragists are individuals who advocate for extending voting rights; in the United States, after African American men gained the right to vote, “suffrage” was primarily understood as women’s suffrage. In contrast, some believe “suffragette” was coined by British reporters in the 1910s to mock the women’s suffragist movement, but the term was later embraced by the same suffragists. The second interpretation suggests that “suffragette” referred to the women in the more radical side of the British female suffragist movement, deriving from a combination of “suffragist” and “cadette”—the French word for young daughter or sister. Under this interpretation in Britain, suffragists were activists employing peaceful methods, while suffragettes were more militant.

Radical suffragists—or suffragettes, based on the second interpretation—were particularly powerful in Great Britain; they became the most famous of the female suffragists due to their radical tactics, which ranged from pasting posters and staging political protests to committing arson against post boxes and buildings. One of the most famous British suffragettes was Emily Davison, who fatally threw herself on the path of the King’s horse during a derby in 1913, showcasing that women would disrupt public life until they achieved suffrage. British women gained the right to vote with the passage of the 1918 Representation of the People Act by the UK Parliament.

By 1960, 129 countries had granted women the right to vote. Female suffrage movements around the world made this mass enfranchisement possible, representing the first wave of feminism; although this wave began in the late 19th century, its roots can be traced back to Enlightenment philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of The Rights of Woman (1792)—the literary foundation for women to gain a voice in the political arena.

From Suffrage to Feminism's Fourth Wave: Through the Lens of the United States

In 1960, right at the close of the first wave of Western feminism, Sirimavo Bandaranaike became the world’s first woman prime minister in Sri Lanka. Her victory shattered the limitations on women’s access to positions of power. The emerging democracies of the developing world pioneered the acceptance of women leaders such as Indira Gandhi in India. It took two more decades for European democracies to catch up, with Margaret Thatcher becoming Britain’s prime minister in 1979.

Feminist movements, as we know them today, started to appear more rapidly after World War II, giving shape to the second wave of feminism during the 1960s. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) was the literary foundation of this wave in the United States. Having won the vote in most democracies around the world, feminists started to shift their discourse towards the role of women in society, shaping their campaigns with a new set of tools and targets inspired by the Civil Rights Movement.

The 1990s saw the emergence of the third wave of feminism, which was marked by a stronger female electorate and intersectional approaches. The increase of female presence across college campuses—women were earning half of all bachelor’s and master’s degrees by 1979—fueled the development of interdisciplinary feminist theories. This wave sparked conversations about sexual harassment and patriarchal abuse. For example, Anita Hill—an attorney who publicly testified that US Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas sexually harassed her—sparked discussions about the unique struggles of Black women. This wave also saw the creation of the Guerilla Girls, an anonymous radical feminist group that utilized art to fight sexism and racism.

For some historians, the third wave of feminism has not ended; rather, it has evolved into a more comprehensive movement that advocates not only for gender equality in the political and social spheres but also for equitable access to healthcare, especially reproductive rights. The rise of technology has defined this fourth wave, enabling feminist movements to amplify their messages more rapidly through social media and digital platforms.

A prominent example is the Me Too movement, founded by Tarana Burke in 2006 to help survivors of sexual assault in their healing processes. In 2017, the #MeToo tag went viral on social media, drawing massive attention to the experiences of women who were survivors of sexual violence. However, feminist movements continued to use “traditional” methods like protesting and distributing posters. Between 3.3 and 4.6 million women participated in the Women’s Marches in January 2017, also advocating for the rights of LGBTQ and racial minorities. Although it originated in the United States, #MeToo went viral globally, trending in every world region and proliferating in regional and linguistic variations. Rooted in the digital connectivity of the world, this fourth wave of feminism is distinctly global.

Each wave of feminism reflects the resources and social changes of its time, pursuing different dimensions of gender equality. The first wave was the colossal first step to enter the political sphere and gain voting rights. Four decades later, the second wave closely followed the Civil Rights Movement while fighting for women’s access to job and educational opportunities. The third wave sparked public discussions about sexism and racism with major legal cases of women reporting sexual harassment and the rise of intersectional feminist theories. Finally, the fourth wave is an extension of the third, marked by the global use of social media and digital platforms to raise awareness about sexual harassment and advocate for reproductive rights. Through protests and powerful rhetoric, feminist movements continue fighting for gender equality and the protection of women’s rights worldwide.

The Future of Feminist Movements: Is Feminism Dying?

Looking at modern feminists and other movements invoking suffrage-era rhetoric, why do contemporary views among young women reflect the decline of feminism, and how might this shift affect global and public opinion on gender equality?

In recent years, feminism has gained a negative connotation among many young women in the West. According to polls in 2019, only one in five women in the United Kingdom and United States identified as a feminist. However, when asked if they supported the idea that men and women should adhere to their traditional roles—men entering the workforce and women staying at home—only eight percent of respondents agreed, so what is happening?

Many women avoid associating with feminism because they perceive it as a movement of women fighting against men rather than advocating for gender equality, often labeling feminists as “feminazis.” The feminist movement has faced criticism that gender equality has already been achieved and the movement no longer aligns with women’s beliefs. However, the core of feminism has not changed; it does not strive for women and men to be the “same” in everything, but to ensure equal rights and access to opportunities. Notably numerous indicators show that these goals are still far away from reach.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to achieve gender equality by 2030. However, according to the latest UN report, “15.4 percent of indicators with data are on track, 61.5 percent are at a moderate distance, and 23.1 percent are far or very far off track from the 2030 targets.” These statistics suggest that progress toward achieving these targets has been slower and more challenging than anticipated, making it unlikely that they will be fully met by the 2030 deadline. Feminism is still necessary for achieving more egalitarian societies, especially in the Global South, where women disproportionately face child marriage, female genital mutilation, poor access to education, and reduced employment opportunities.

In the political arena, women vote at higher rates than men in many countries, including the United States. However, this participation does not translate into more women accessing political positions. Today, many countries continue to fight for more female representation in their legislatures. For example, the Japanese Association of Women in Politics encourages women to participate more vigorously in national politics; only 16 percent of seats in the Japanese parliament belong to women. Many other countries have low female representation in their governments, and over 100 countries have not had a woman as head of state. These data undermine the argument that gender equality has been achieved.

The Future of Female Politics

“About a third of UN member states have ever had a woman leader.” This is the headline of the October 2024 report in politics and policy from the Pew Research Center, which observes female leadership across the globe. Although much has been done to increase women’s participation in politics, as highlighted in this article, significant work remains to open top political leadership positions to women. The United Nations stated that—if the present rate of progress continues—it will take “140 years for women to be represented equally in positions of power and leadership in the workplace, and 47 years to achieve equal representation in national parliaments.” These statistics further highlight the need for women’s movements to continue working towards gender equality.

The legacy of the suffragists and suffragettes still has a considerable impact on the political sphere of modern feminism. Their tactics—like generating support in public opinion through the dissemination of powerful messages—are used to attract attention to gender inequality problems and push for legislative reforms. Activist movements fighting for other causes, like Just Stop Oil, have taken “tactics directly from the suffragette playbook,” showcasing the enduring vision of the women who advocated for female suffrage.

It remains crucial to close global gender gaps in education, economic opportunities, and social spheres. The political realm plays a pivotal role by creating and enforcing laws that protect and uplift women. Over a century ago, political feminist movements were catalysts for change, advancing the debate in social spaces. The history of feminism should remain central to the causes of modern feminists, honoring the pioneers who secured women’s right to vote and paved the way for a more equal world.